Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

May-June 2023

If you were dropped onto this planet and landed at McCormick Place in the heart of Chicago in the middle of March, you would probably conclude that planet Earth had been overrun by robots. Everywhere you turned on the ProMat conference floor, there was a robot lifting something, putting something away, or carrying something to another location. But, despite a conference hall overrun by technology, the on-the-ground reality is a bit different. Not so long ago, commercial real estate firm Prologis estimated the number of facilities with any type of automation at about 10%. But that is changing—quickly. A recent report from JLL found that one-in-two… Browse this issue archive.Need Help? Contact customer service 847-559-7581 More options

The editor of Supply Chain Management Review made an unusual request for the May 2023 edition. He asked this married couple to write an article about psychologic principles to empower negotiations. This topic does fit us. Mark regularly teaches conference audiences and corporate procurement groups on best practices in negotiations. Melanie is a medical doctor practicing in the field of psychiatry and teaching at the undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate levels as a tenured professor, as well as regularly speaking in the educational and medical communities on matters relating to intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships. So, let’s get started.

The place of negotiations in today’s procurement toolbox

Despite all the “eTools” in today’s supply management toolkit, negotiations are still the most utilized way to establish (and improve) complex business relationships. Most senior supply management professionals agree that negotiations are the preferred methodology for dealing with alliance and strategic types of supplier relationships—ones that account for a large proportion of supply chain expense.

This truth has been further compounded during the last two years as the balance of power in typical commercial relationships has shifted toward the suppliers, in combination with COVID supply chain disruptions and energy-induced inflationary price increases.

Let’s face it, a greater portion of the average firm’s procurement relationships have been exposed to renegotiations than ever before. It was decades ago that we last saw force majeure language being deployed in the commercial contracting environment anywhere close to current levels.

With so much pressure on buyer/supplier relationships, how can procurement leaders be more successful in the process of negotiations? How can professionals expand the power of negotiations beyond the boundaries of MDO (most desirable outcome), LAA (least acceptable agreement), and BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement)? A greater understanding and incorporation of psychological elements may be the key to success.

Jack Lew, the 76th U.S. treasury secretary once observed that: “The most critical thing in a negotiation is to get inside your opponent’s head and figure out what he really wants.” This article will discuss four principles that influence the mind of our counterpart and our relationship with them. They are as follows.

- Be prepared—get beyond positions by understanding the supplier’s needs;

- appreciate our counterpart’s personality traits and our own;

- reading (and sending) non-spoken body language; and

- using interrogatives to appropriately shift the other party’s paradigm view.

Technique #1. Be prepared: Getting beyond positions by understanding the supplier’s needs

Too often, the buyer and seller in a commercial negotiation adopt positions from the first interchange. Being positional is illustrated by an unwillingness to consider other alternatives, and often results in limited accomplishment through the negotiation process. But the most-skilled negotiators realize that willingness to explore a variety of options will drive better outcomes. We can be more successful in doing this when we understand the needs of the supplier.

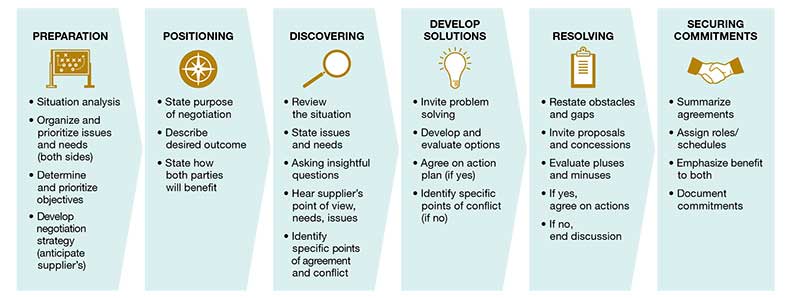

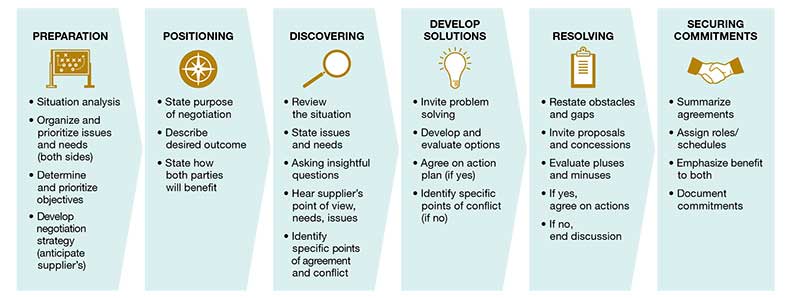

This involves some detective work up front. It has been said that “preparation should take 75% of the overall time in a negotiation process.” This is absolutely true. The better-prepared our negotiation team is, the better the outcome of the negotiation. The phases of a successful negotiation can be seen in the Figure 1 process chart.

Figure 1: Negotiation process

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023, Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

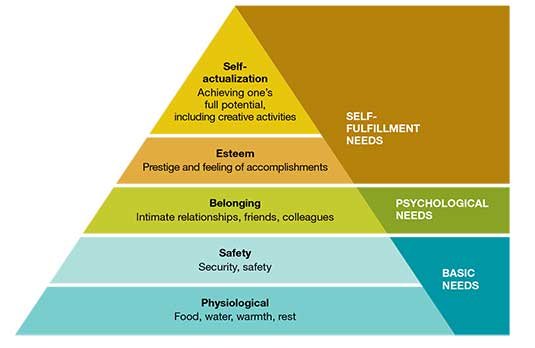

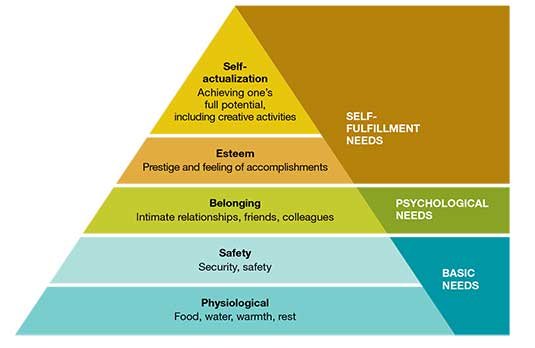

One method of understanding a supplier’s basic needs is via advanced detective work into the supplier’s business goals and their negotiation team members’ personal motivations. Ury, in “Getting to Yes,” encourages us to think of wise negotiation solutions in terms of reconciling “interests, not positions.” So, while a supplier may be committed to their position, our taking time to discover their interests (needs) can shift the negotiation in a positive direction. The most powerful interests are often basic human needs described by Maslow in his famous hierarchy (see Figure 2).

Maslow’s hierarchy anticipates that human beings will prioritize basic needs and psychological needs first. Once we have a source for nutrition, we seek stability and safety; often found in a regular job and a place to live. Once safety is established with a steady source of income, most people seek to belong socially; belonging as part of a work team, religious body, etc. But Maslow also recognized that human beings are willing to step out on their own when accomplishment can bring a level of personal achievement. And finally, some people are motivated to attain an even higher level of fulfillment called self-actualization illustrated by motivation to innovate.

With some advanced detective work, the procurement negotiation team may be able to identify the level of need fulfillment at which the opposing negotiation team is operating.

- Is the supplier organization struggling to survive financially? Could this contract move them toward improved health (safety need)?

- Has the supplier’s negotiation team been told by their CEO that getting an agreement with your firm is a requirement for their annual sales recognition award program (belonging need)?

- Would the ability to list your firm as a customer increase the supplier’s credibility in the marketplace (esteem need)?

- Might being selected to defend your firm in a key lawsuit allow a law firm to set legal precedence (self-actualization need)?

To estimate the supplier’s level of need fulfillment, more detective work is needed. There is no good excuse for being less-prepared than our sales counterparts.

Figure 2: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023,Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

During a break in a $100 million medical equipment purchase negotiation process, a hospital group’s lead negotiator noticed that one of the manufacturer’s

negotiation team members had left their notebook open. The first page was a copy of the hospital’s main negotiator’s LinkedIn profile page covered by handwritten notes. The message was clear; the supplier had done their homework. Shame on the buying organization for not exercising the same due diligence.

The procurement team can easily spend time doing the following before a key negotiation.

- Explore the supplier’s website to learn about product lines, customers, and business announcements.

- Understand trends in the supplier’s major cost drivers (for example, if chromalloy steel is a component in the supplier’s products, you’ll need to understand the price trends leading up to, and forecasted into the future, for chromalloy steel).

- If publicly traded, download the supplier’s annual financial reports to understand their stated and planned business direction. If you are responsible for a key supplier relationship, just buy a share of the firm’s stock in your own brokerage account to automatically receive these reports. In addition, you can download stock analyst reports that provide insight into financial and business challenges/opportunities that may exist for the supplier.

- Track essential data elements about the supplier. It is especially important to have real-time visibility into financial stability, negative news media exposure, bankruptcies, lien filings, legal judgements, criminality reports, presence on governmental watchlists, etc. [Author’s note: email Mark for the name of a provider that will track all these for every one of your suppliers at no cost.]

- Call any customer references provided by the supplier (during RFP or standalone processes). Use these conversations to ask more than “is this a good supplier?” Instead, leverage the discussion to learn about the supplier’s potential needs like typical approach during negotiations, tactics to be prepared for, details of cost structures, concessions gained by the reference, etc.

- Visit the LinkedIn profile page of each person on the supplier’s negotiation team to understand their backgrounds and potential perspectives. Where did they attend university? What degrees do they hold? Where do they live? Married? Children? Where else have they worked? What social organizations do they belong to? Who do they follow online?

Technique #2. Appreciating our counterparty’s personality traits as well as our own

The term personality describes the unique patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish one person from others. It is a product of both our biology and environment.

Those in the field of psychology often utilize five elemental components of human personality known as the Big 5, which is widely accepted today because this model presents a framework for understanding the main dimensional traits of personality. These traits are often easily remembered by use of the acronym OCEAN.

- O = Openness

- C = Conscientiousness

- E = Extraversion

- A = Agreeableness

- N = Neuroticism

Experts (Fiske, Norman, Smith, Goldberg, McCrae, Costa) found that these OCEAN traits are an accurate portrait of the human personality and are often applied successfully across cultures. These elements can be evaluated along a range between two extremes and recognizes that for each, real persons lie somewhere between the extreme ends of each range. Think of it this way. “The degree to which I am _______.”

Guess what? We all have some degree of each one of these OCEAN elements. Take a few minutes sometime and take a look at yourself through the lens of this tool and see what you discover. Ask yourself how your unique blend of these traits can serve to limit or empower your role as a business person; and especially your effectiveness as a negotiator.

How can the Big 5 be an added tool in the negotiation collaboration with our counterparts? Recognizing that it is not used to diagnose but is used as a reflective tool is important. For instance, in the field of organizational behavior, tests based on the Big 5 are used in employee assessment tests for purposes such as understanding and guiding individual success within the team.

But based upon your past experiences with the supplier’s representatives, you may be able to use OCEAN to make some assumptions that influence how you sequence the topics in a negotiation, ask and answer questions, challenge the status quo, etc. How can the negotiation be strategically structured to best impact the opponent given their personal traits?

You may be inclined, at first glance, to think it best to be extremely high in agreeableness and that there is no significant place for a low score in that area. Let’s take a look. Because agreeableness refers to a desire to keep things running smoothly/a focus on the other/trusting, a higher score might imply that you are an adapter while a lower score may indicate that you are a challenger. Might there be an appropriate place for each? Let’s look at one more. A lower score in openness, meaning a focus on the new/curiosity, might signify persevering traits. A higher score may suggest exploring traits. Again, the perfect score may not exist with this tool. However, understanding the score may be a worthwhile exercise to enhance our negotiations because we better understand ourselves and others.

We have recognized the value of a better appreciation of personality traits and styles as a key to our negotiation process. Another approach that personality research has provided is emotional intelligence or emotional quotient (EQ). We see Maslow’s hand once again in his early focus on emotional strength, but it was in 1990 that Salovey and Mayer described emotional intelligence as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.” In the negotiation arena, we can see this fleshed out in our ability to perceive, interpret, demonstrate, control, and use emotions to relate to others constructively. The topic of emotional intelligence has continued to capture interest in many fields, including business, as the ability to express and control our own emotions is essential. Equally important is the ability to understand, interpret, and respond to the emotions of others (i.e., the supplier).

What are emotional components we should be evaluating before, during and after negotiations with a supplier?

- Perceiving emotion. Accurate perception is key; verbal and non-verbal language need consideration.

- Reasoning with emotion. Emotions promote thinking and cognitive activity; emotions play a part in prioritizing what we attend to and vice versa.

- Understanding emotions. Our perceived emotions can carry a variety of meanings.

- Managing emotions. Regulation of and responding appropriately to emotion in ourselves and others is vital.

Some of us come by these skills naturally, while others would like to develop EQ skills more fully. The great news is that there is good data to suggest that EQ training can improve EQ abilities in workplace business settings.

Tips for us all include the following.

- Listen, listen, listen. Actively give full attention to what others are telling us both verbally and non-verbally.

- Reflect, reflect, reflect. Assess the verbal and non-verbal messages you are delivering.

- Attend. Consider your emotional state and how that informs your behavior.

- Get feedback. As the proverb says: Iron sharpens iron. Appropriate and qualified feedback can facilitate further insight in both EQ areas as well as personality trait areas.

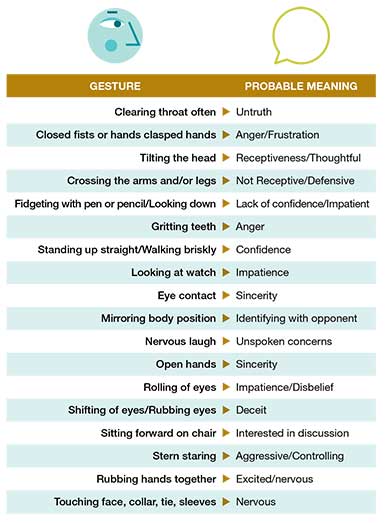

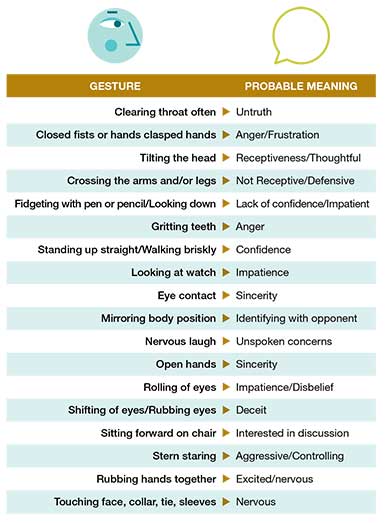

Technique #3. Reading (and sending) non-spoken body language

Peter Drucker once pointed out: “The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn’t said.” Behavioral psychologist Dr. Albert Mehrabian’s extensive research on nonverbal communications resulted in the “7-38-55 Rule,” whereby only 7% of all communication is done through purely verbal communication, whereas the nonverbal component of our daily communication, such as the tonality of our voice and body language, make up 38% and 55% respectively.

While this formula applies to certain situations, it does not claim to apply to all. It does remind us that a single gesture or comment does not necessarily mean something. But it certainly suggests that we pay attention to nonverbal cues to get an accurate understanding of a counterparty’s communication being delivered.

So how can that translate into a formal commercial negotiation process? We may be missing the important clues as to what the counterparty is thinking. For some typical gestures, Figure 3 illustrates probable meanings.

An obvious takeaway is that the medium we choose for a negotiation affects the nonverbal information we perceive. In order of preference, negotiation mediums rank in the following order: (1) negotiations in person, (2) web video [i.e., Zoom, Teams, etc.], (3) telephone, (4) email/text. The obvious difference is the curtailment of nonverbal cues as proximity shrinks.

Figure 3: Non-verbal cues

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023,Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

A number of years ago, Mark successfully led a team of consultants in helping a Top 5 global tire manufacturer reduce their indirect expenditures by $25 million. One key opportunity was to re-negotiate a $20 million contract for loading dock services. On the appointed day, the president and the EVP of the provider company flew into town on a corporate jet to begin negotiations with Mark and his client in an early afternoon meeting. The negotiations began with Mark’s procurement client starting to explain that the goal was to restructure the relationship from an hourly rate per loading dock contractor into a flat rate for filling different shipping containers (railroad cars, TL and LTL). But Mark noticed uncomfortable body language from the supplier’s executives. So, he paused the negotiation, and inquired whether they were feeling discomfort.

The supplier’s president shared that the tire company was 90+ days in arrears on $250,000 in invoices. That morning, they had met with the tire manufacturer’s accounting VP about the overdue invoices, and had been told: “We’ll get it cleaned up eventually. Just be patient.” That had shocked the two executives.

The tire company’s procurement leader responded by saying he would try and work with the accounting VP to clean up the situation. Then he suggested they continue the rate discussion. But Mark stopped the negotiation again, and asked whether the executives could be back in the area the next week. They said yes. To his client’s consternation, Mark delayed the rest of the negotiation until the following week.

The next week, the supplier’s president was handed a check for the overdue amount. Mark and his client then proceeded to negotiate a win-win agreement that achieved 33% less cost per shipping unit for the tire company as well as 30% higher productivity from the loading dock contractor. It pays to watch body language.

Technique #4. Using interrogatives to appropriately shift the other party’s paradigm

Big words in this title, but simple concepts. An interrogative is simply to ask a question. Same Latin root word as interrogate. Asking insightful questions is a key to the third phase of a successful negotiation. The term paradigm is simply how a negotiation party views a topic at hand—it’s their perspective. Getting the other party to answer key questions can sometimes change their perspective on the negotiable elements.

The best negotiators are clever interrogators. They listen carefully to the other party’s answers. They seem to follow the old guideline that “God gave us two ears and one mouth, and we should use them proportionately.”

The authors dated long distance (Ohio and California) for more than a year before getting married. That meant they spent a lot of time talking on the phone. They both grew in their conversational abilities, but Mark grew more. Part of his growth was learning ways to pose Melanie better interrogatives. For example, early in their relationship, Mark might begin a conversation asking: “Did you have a good day today?” That left Melanie with two choices—yes or no. Then awkward silence. A better question might have been: “What was the most interesting thing about your day?”

How often has an unexperienced procurement person asked a dead-end yes or no question like: “Can’t you do better on the price?” Then they wait for the answer, until a smug supplier sales executive just says no.

There are a variety of general question styles that Mark’s colleagues train clients to use to achieve better results (they also train procurement leaders on how to respond to tough questions from suppliers).

- Pre-questions can set parameters for a negotiation session. For example, sending an email to the supplier like the following: “We’re looking forward to meeting with your team next week. Please email me in the next couple of days to let us know what your goals, objectives, and timelines are and how you propose we can best resolve the product quality issues. This will help me prepare an agenda for both our teams.”

- Suggestive questions can be designed to lead an opponent down pathways attractive to the buying organization. For example: “Would X work better for you or Y?” The trick is that both X and Y are options attractive to the buyer. By answering the question as asked, the seller has already compromised their position.

- Leading questions are typically answered with a yes or no (sometimes leading to further clarification). They can force the other party into a corner where they must reveal something foundational to the rest of the negotiation. Examples might be:

“You do have some flexibility on the price,don’t you?”

“You do want a five-year agreement, don’t you?”

“Your firm doesn’t have any problem with transferring IP rights to our firm, do you?”

- “What’s in it for me” questions cut right to the chase and can sometimes shift the seller away from a strong initial position to one of trying to justify their suppositions. One example is: “Our team has spent several weeks trying to work out details of a potential agreement with your firm. But before we spend any more time negotiating, we’d like your firm to restate the reasons we should be moving forward with this deal. After all the concessions, what’s really in it for us?

- “What-if” questions are beautiful questions to ask. The phrase is effective because it extracts a discussion from the opponent about a concept … without getting positional. An example might be, “What if we both put inspectors on site during the last three months of the construction project?”

An expanded approach to the interrogative concept is that of motivational interviewing (MI) that nicely intersects with the negotiation flow chart at the beginning of this article. Some applicable techniques borrowed from MI may enable a negotiator to creatively facilitate a change process together with the supplier’s team. An appropriate paradigm shift may be the result by coming to a collaborative realization of a different pathway.

The foundation of motivational interviewing is that it is impossible to have an unmotivated counterparty. Every human being is motivated toward something. The question is what? Motivational interviewing is a person-centered, goal-oriented approach for facilitating change through exploring and resolving ambivalence. This dynamic counseling approach was first established by Rosengren and Miller to help patients make better personal choices. Some of its techniques are now successfully applied to other fields such as business and education. As a psychiatrist, Dr. Melanie is quite familiar with MI’s successful use in doctor-patient relationships as well as educator-student interactions.

What are some MI techniques that provide opportunities in a negotiation pathway? MI is a negotiator’s friend by being an additional communication tool. It encourages a collaborative conversation to strengthen motivation toward growth and change; it can move a situation from why to how. MI provides intrinsic and extrinsic motivation toward change behavior, invaluable in any negotiation process. How? It honors individuals as well as partnership. It recognizes strengths/competencies to scaffold growth and change and enhances interpersonal collaboration.

Supply chain negotiators can use the process of motivational interviewing through a sequence of steps abbreviated by the acronym of OARS.

- O = Open-ended questions. These can lead the supplier in identifying possible solutions.

- Recognize a problem: How do you feel about the large number of late deliveries this month?

- Express a concern: What worries do you have about the rising diesel costs?

- Intention to change: What would you like to see happen with our company’s expansion into the Northeast?

- Recognize optimism: What makes you think that now is a good time to try something different?

- Elaboration: In what ways? Tell me more. What does that look like? (Listen for ways the supplier may be willing make a shift.)

- Favorites: “On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not at all ready to make a change and 10 is ready to make a change, where are you right now?” Note: It is rare to hear a response of 1. So, even if there is a 2 or 3 given, this provides a great opportunity to ask: “Why are you at a 2 and not a 1?” “What might happen that could move you from the 2 to a 4?” “What may happen if things continue as they are?” “If you were successful in making the changes you want, what would be different?”

A = Affirmations. Genuinely notice and appreciate specific strengths/actions raised in the supplier’s question responses. Procurement’s negotiator needs to recognize value by tying pros and cons together. Even if all of the elements in the supplier’s responses are not positive, take time to express authentic appreciation for the positives that their negotiator does raise. Doing this sets up collaboration and trust.

R = Reflections. These are statements NOT questions. They often yield more info and deeper understanding as they reinforce correct perceptions of the supplier’s responses.

- Hear what they are saying.

- Make an educated statement at their meaning and / verbalize this perception in a statement form such as: “It sounds like you are ready to reduce our pricing if we can simplify our quality inspections.” “So, you are saying that you are having trouble with the availability of copper components.” Or, “It sounds like you are feeling frustrated with our habit of placing multiple orders once monthly rather than spreading them out weekly.”

- Wait for validation. Don’t say anything else until the supplier responds. In this case, silence is golden.

- S = Summarization. Key elements of commonality can be highlighted that facilitate strategic agreement. Summarizing points of agreement helps both parties recall and reflect upon the key points. Emphasize your counterpart’s comments and views that can move them emotionally and logically to better solutions. Focus on fundamental motivations and interest.

As Marc Randolph, the founder of Netflix, once said: “Negotiation is empathy. It’s almost trite to say that if you can’t put yourself in the seat of the other person you’re speaking with, you’re not going to do well.”

The ability to understand a supplier’s psych and influence what they are thinking is key to a successful negotiation. Each of the techniques in this article can empower the phases of a productive supplier interchange. These four methods can help to alter a supplier’s perceptions in the negotiation process. We hope that they prove to be useful to the readers of this article.

SC

MR

Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

May-June 2023

If you were dropped onto this planet and landed at McCormick Place in the heart of Chicago in the middle of March, you would probably conclude that planet Earth had been overrun by robots. Everywhere you turned on the… Browse this issue archive. Access your online digital edition. Download a PDF file of the May-June 2023 issue.The editor of Supply Chain Management Review made an unusual request for the May 2023 edition. He asked this married couple to write an article about psychologic principles to empower negotiations. This topic does fit us. Mark regularly teaches conference audiences and corporate procurement groups on best practices in negotiations. Melanie is a medical doctor practicing in the field of psychiatry and teaching at the undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate levels as a tenured professor, as well as regularly speaking in the educational and medical communities on matters relating to intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships. So, let’s get started.

The place of negotiations in today’s procurement toolbox

Despite all the “eTools” in today’s supply management toolkit, negotiations are still the most utilized way to establish (and improve) complex business relationships. Most senior supply management professionals agree that negotiations are the preferred methodology for dealing with alliance and strategic types of supplier relationships—ones that account for a large proportion of supply chain expense.

This truth has been further compounded during the last two years as the balance of power in typical commercial relationships has shifted toward the suppliers, in combination with COVID supply chain disruptions and energy-induced inflationary price increases.

Let’s face it, a greater portion of the average firm’s procurement relationships have been exposed to renegotiations than ever before. It was decades ago that we last saw force majeure language being deployed in the commercial contracting environment anywhere close to current levels.

With so much pressure on buyer/supplier relationships, how can procurement leaders be more successful in the process of negotiations? How can professionals expand the power of negotiations beyond the boundaries of MDO (most desirable outcome), LAA (least acceptable agreement), and BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement)? A greater understanding and incorporation of psychological elements may be the key to success.

Jack Lew, the 76th U.S. treasury secretary once observed that: “The most critical thing in a negotiation is to get inside your opponent’s head and figure out what he really wants.” This article will discuss four principles that influence the mind of our counterpart and our relationship with them. They are as follows.

- Be prepared—get beyond positions by understanding the supplier’s needs;

- appreciate our counterpart’s personality traits and our own;

- reading (and sending) non-spoken body language; and

- using interrogatives to appropriately shift the other party’s paradigm view.

Technique #1. Be prepared: Getting beyond positions by understanding the supplier’s needs

Too often, the buyer and seller in a commercial negotiation adopt positions from the first interchange. Being positional is illustrated by an unwillingness to consider other alternatives, and often results in limited accomplishment through the negotiation process. But the most-skilled negotiators realize that willingness to explore a variety of options will drive better outcomes. We can be more successful in doing this when we understand the needs of the supplier.

This involves some detective work up front. It has been said that “preparation should take 75% of the overall time in a negotiation process.” This is absolutely true. The better-prepared our negotiation team is, the better the outcome of the negotiation. The phases of a successful negotiation can be seen in the Figure 1 process chart.

Figure 1: Negotiation process

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023, Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

One method of understanding a supplier’s basic needs is via advanced detective work into the supplier’s business goals and their negotiation team members’ personal motivations. Ury, in “Getting to Yes,” encourages us to think of wise negotiation solutions in terms of reconciling “interests, not positions.” So, while a supplier may be committed to their position, our taking time to discover their interests (needs) can shift the negotiation in a positive direction. The most powerful interests are often basic human needs described by Maslow in his famous hierarchy (see Figure 2).

Maslow’s hierarchy anticipates that human beings will prioritize basic needs and psychological needs first. Once we have a source for nutrition, we seek stability and safety; often found in a regular job and a place to live. Once safety is established with a steady source of income, most people seek to belong socially; belonging as part of a work team, religious body, etc. But Maslow also recognized that human beings are willing to step out on their own when accomplishment can bring a level of personal achievement. And finally, some people are motivated to attain an even higher level of fulfillment called self-actualization illustrated by motivation to innovate.

With some advanced detective work, the procurement negotiation team may be able to identify the level of need fulfillment at which the opposing negotiation team is operating.

- Is the supplier organization struggling to survive financially? Could this contract move them toward improved health (safety need)?

- Has the supplier’s negotiation team been told by their CEO that getting an agreement with your firm is a requirement for their annual sales recognition award program (belonging need)?

- Would the ability to list your firm as a customer increase the supplier’s credibility in the marketplace (esteem need)?

- Might being selected to defend your firm in a key lawsuit allow a law firm to set legal precedence (self-actualization need)?

To estimate the supplier’s level of need fulfillment, more detective work is needed. There is no good excuse for being less-prepared than our sales counterparts.

Figure 2: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023,Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

During a break in a $100 million medical equipment purchase negotiation process, a hospital group’s lead negotiator noticed that one of the manufacturer’s

negotiation team members had left their notebook open. The first page was a copy of the hospital’s main negotiator’s LinkedIn profile page covered by handwritten notes. The message was clear; the supplier had done their homework. Shame on the buying organization for not exercising the same due diligence.

The procurement team can easily spend time doing the following before a key negotiation.

- Explore the supplier’s website to learn about product lines, customers, and business announcements.

- Understand trends in the supplier’s major cost drivers (for example, if chromalloy steel is a component in the supplier’s products, you’ll need to understand the price trends leading up to, and forecasted into the future, for chromalloy steel).

- If publicly traded, download the supplier’s annual financial reports to understand their stated and planned business direction. If you are responsible for a key supplier relationship, just buy a share of the firm’s stock in your own brokerage account to automatically receive these reports. In addition, you can download stock analyst reports that provide insight into financial and business challenges/opportunities that may exist for the supplier.

- Track essential data elements about the supplier. It is especially important to have real-time visibility into financial stability, negative news media exposure, bankruptcies, lien filings, legal judgements, criminality reports, presence on governmental watchlists, etc. [Author’s note: email Mark for the name of a provider that will track all these for every one of your suppliers at no cost.]

- Call any customer references provided by the supplier (during RFP or standalone processes). Use these conversations to ask more than “is this a good supplier?” Instead, leverage the discussion to learn about the supplier’s potential needs like typical approach during negotiations, tactics to be prepared for, details of cost structures, concessions gained by the reference, etc.

- Visit the LinkedIn profile page of each person on the supplier’s negotiation team to understand their backgrounds and potential perspectives. Where did they attend university? What degrees do they hold? Where do they live? Married? Children? Where else have they worked? What social organizations do they belong to? Who do they follow online?

Technique #2. Appreciating our counterparty’s personality traits as well as our own

The term personality describes the unique patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish one person from others. It is a product of both our biology and environment.

Those in the field of psychology often utilize five elemental components of human personality known as the Big 5, which is widely accepted today because this model presents a framework for understanding the main dimensional traits of personality. These traits are often easily remembered by use of the acronym OCEAN.

- O = Openness

- C = Conscientiousness

- E = Extraversion

- A = Agreeableness

- N = Neuroticism

Experts (Fiske, Norman, Smith, Goldberg, McCrae, Costa) found that these OCEAN traits are an accurate portrait of the human personality and are often applied successfully across cultures. These elements can be evaluated along a range between two extremes and recognizes that for each, real persons lie somewhere between the extreme ends of each range. Think of it this way. “The degree to which I am _______.”

Guess what? We all have some degree of each one of these OCEAN elements. Take a few minutes sometime and take a look at yourself through the lens of this tool and see what you discover. Ask yourself how your unique blend of these traits can serve to limit or empower your role as a business person; and especially your effectiveness as a negotiator.

How can the Big 5 be an added tool in the negotiation collaboration with our counterparts? Recognizing that it is not used to diagnose but is used as a reflective tool is important. For instance, in the field of organizational behavior, tests based on the Big 5 are used in employee assessment tests for purposes such as understanding and guiding individual success within the team.

But based upon your past experiences with the supplier’s representatives, you may be able to use OCEAN to make some assumptions that influence how you sequence the topics in a negotiation, ask and answer questions, challenge the status quo, etc. How can the negotiation be strategically structured to best impact the opponent given their personal traits?

You may be inclined, at first glance, to think it best to be extremely high in agreeableness and that there is no significant place for a low score in that area. Let’s take a look. Because agreeableness refers to a desire to keep things running smoothly/a focus on the other/trusting, a higher score might imply that you are an adapter while a lower score may indicate that you are a challenger. Might there be an appropriate place for each? Let’s look at one more. A lower score in openness, meaning a focus on the new/curiosity, might signify persevering traits. A higher score may suggest exploring traits. Again, the perfect score may not exist with this tool. However, understanding the score may be a worthwhile exercise to enhance our negotiations because we better understand ourselves and others.

We have recognized the value of a better appreciation of personality traits and styles as a key to our negotiation process. Another approach that personality research has provided is emotional intelligence or emotional quotient (EQ). We see Maslow’s hand once again in his early focus on emotional strength, but it was in 1990 that Salovey and Mayer described emotional intelligence as “the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions.” In the negotiation arena, we can see this fleshed out in our ability to perceive, interpret, demonstrate, control, and use emotions to relate to others constructively. The topic of emotional intelligence has continued to capture interest in many fields, including business, as the ability to express and control our own emotions is essential. Equally important is the ability to understand, interpret, and respond to the emotions of others (i.e., the supplier).

What are emotional components we should be evaluating before, during and after negotiations with a supplier?

- Perceiving emotion. Accurate perception is key; verbal and non-verbal language need consideration.

- Reasoning with emotion. Emotions promote thinking and cognitive activity; emotions play a part in prioritizing what we attend to and vice versa.

- Understanding emotions. Our perceived emotions can carry a variety of meanings.

- Managing emotions. Regulation of and responding appropriately to emotion in ourselves and others is vital.

Some of us come by these skills naturally, while others would like to develop EQ skills more fully. The great news is that there is good data to suggest that EQ training can improve EQ abilities in workplace business settings.

Tips for us all include the following.

- Listen, listen, listen. Actively give full attention to what others are telling us both verbally and non-verbally.

- Reflect, reflect, reflect. Assess the verbal and non-verbal messages you are delivering.

- Attend. Consider your emotional state and how that informs your behavior.

- Get feedback. As the proverb says: Iron sharpens iron. Appropriate and qualified feedback can facilitate further insight in both EQ areas as well as personality trait areas.

Technique #3. Reading (and sending) non-spoken body language

Peter Drucker once pointed out: “The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn’t said.” Behavioral psychologist Dr. Albert Mehrabian’s extensive research on nonverbal communications resulted in the “7-38-55 Rule,” whereby only 7% of all communication is done through purely verbal communication, whereas the nonverbal component of our daily communication, such as the tonality of our voice and body language, make up 38% and 55% respectively.

While this formula applies to certain situations, it does not claim to apply to all. It does remind us that a single gesture or comment does not necessarily mean something. But it certainly suggests that we pay attention to nonverbal cues to get an accurate understanding of a counterparty’s communication being delivered.

So how can that translate into a formal commercial negotiation process? We may be missing the important clues as to what the counterparty is thinking. For some typical gestures, Figure 3 illustrates probable meanings.

An obvious takeaway is that the medium we choose for a negotiation affects the nonverbal information we perceive. In order of preference, negotiation mediums rank in the following order: (1) negotiations in person, (2) web video [i.e., Zoom, Teams, etc.], (3) telephone, (4) email/text. The obvious difference is the curtailment of nonverbal cues as proximity shrinks.

Figure 3: Non-verbal cues

Source: Advanced Procurement Negotiation Training Masterclass, 2000-2023,Strategic Procurement Solutions LLC

A number of years ago, Mark successfully led a team of consultants in helping a Top 5 global tire manufacturer reduce their indirect expenditures by $25 million. One key opportunity was to re-negotiate a $20 million contract for loading dock services. On the appointed day, the president and the EVP of the provider company flew into town on a corporate jet to begin negotiations with Mark and his client in an early afternoon meeting. The negotiations began with Mark’s procurement client starting to explain that the goal was to restructure the relationship from an hourly rate per loading dock contractor into a flat rate for filling different shipping containers (railroad cars, TL and LTL). But Mark noticed uncomfortable body language from the supplier’s executives. So, he paused the negotiation, and inquired whether they were feeling discomfort.

The supplier’s president shared that the tire company was 90+ days in arrears on $250,000 in invoices. That morning, they had met with the tire manufacturer’s accounting VP about the overdue invoices, and had been told: “We’ll get it cleaned up eventually. Just be patient.” That had shocked the two executives.

The tire company’s procurement leader responded by saying he would try and work with the accounting VP to clean up the situation. Then he suggested they continue the rate discussion. But Mark stopped the negotiation again, and asked whether the executives could be back in the area the next week. They said yes. To his client’s consternation, Mark delayed the rest of the negotiation until the following week.

The next week, the supplier’s president was handed a check for the overdue amount. Mark and his client then proceeded to negotiate a win-win agreement that achieved 33% less cost per shipping unit for the tire company as well as 30% higher productivity from the loading dock contractor. It pays to watch body language.

Technique #4. Using interrogatives to appropriately shift the other party’s paradigm

Big words in this title, but simple concepts. An interrogative is simply to ask a question. Same Latin root word as interrogate. Asking insightful questions is a key to the third phase of a successful negotiation. The term paradigm is simply how a negotiation party views a topic at hand—it’s their perspective. Getting the other party to answer key questions can sometimes change their perspective on the negotiable elements.

The best negotiators are clever interrogators. They listen carefully to the other party’s answers. They seem to follow the old guideline that “God gave us two ears and one mouth, and we should use them proportionately.”

The authors dated long distance (Ohio and California) for more than a year before getting married. That meant they spent a lot of time talking on the phone. They both grew in their conversational abilities, but Mark grew more. Part of his growth was learning ways to pose Melanie better interrogatives. For example, early in their relationship, Mark might begin a conversation asking: “Did you have a good day today?” That left Melanie with two choices—yes or no. Then awkward silence. A better question might have been: “What was the most interesting thing about your day?”

How often has an unexperienced procurement person asked a dead-end yes or no question like: “Can’t you do better on the price?” Then they wait for the answer, until a smug supplier sales executive just says no.

There are a variety of general question styles that Mark’s colleagues train clients to use to achieve better results (they also train procurement leaders on how to respond to tough questions from suppliers).

- Pre-questions can set parameters for a negotiation session. For example, sending an email to the supplier like the following: “We’re looking forward to meeting with your team next week. Please email me in the next couple of days to let us know what your goals, objectives, and timelines are and how you propose we can best resolve the product quality issues. This will help me prepare an agenda for both our teams.”

- Suggestive questions can be designed to lead an opponent down pathways attractive to the buying organization. For example: “Would X work better for you or Y?” The trick is that both X and Y are options attractive to the buyer. By answering the question as asked, the seller has already compromised their position.

- Leading questions are typically answered with a yes or no (sometimes leading to further clarification). They can force the other party into a corner where they must reveal something foundational to the rest of the negotiation. Examples might be:

“You do have some flexibility on the price,don’t you?”

“You do want a five-year agreement, don’t you?”

“Your firm doesn’t have any problem with transferring IP rights to our firm, do you?”

- “What’s in it for me” questions cut right to the chase and can sometimes shift the seller away from a strong initial position to one of trying to justify their suppositions. One example is: “Our team has spent several weeks trying to work out details of a potential agreement with your firm. But before we spend any more time negotiating, we’d like your firm to restate the reasons we should be moving forward with this deal. After all the concessions, what’s really in it for us?

- “What-if” questions are beautiful questions to ask. The phrase is effective because it extracts a discussion from the opponent about a concept … without getting positional. An example might be, “What if we both put inspectors on site during the last three months of the construction project?”

An expanded approach to the interrogative concept is that of motivational interviewing (MI) that nicely intersects with the negotiation flow chart at the beginning of this article. Some applicable techniques borrowed from MI may enable a negotiator to creatively facilitate a change process together with the supplier’s team. An appropriate paradigm shift may be the result by coming to a collaborative realization of a different pathway.

The foundation of motivational interviewing is that it is impossible to have an unmotivated counterparty. Every human being is motivated toward something. The question is what? Motivational interviewing is a person-centered, goal-oriented approach for facilitating change through exploring and resolving ambivalence. This dynamic counseling approach was first established by Rosengren and Miller to help patients make better personal choices. Some of its techniques are now successfully applied to other fields such as business and education. As a psychiatrist, Dr. Melanie is quite familiar with MI’s successful use in doctor-patient relationships as well as educator-student interactions.

What are some MI techniques that provide opportunities in a negotiation pathway? MI is a negotiator’s friend by being an additional communication tool. It encourages a collaborative conversation to strengthen motivation toward growth and change; it can move a situation from why to how. MI provides intrinsic and extrinsic motivation toward change behavior, invaluable in any negotiation process. How? It honors individuals as well as partnership. It recognizes strengths/competencies to scaffold growth and change and enhances interpersonal collaboration.

Supply chain negotiators can use the process of motivational interviewing through a sequence of steps abbreviated by the acronym of OARS.

- O = Open-ended questions. These can lead the supplier in identifying possible solutions.

- Recognize a problem: How do you feel about the large number of late deliveries this month?

- Express a concern: What worries do you have about the rising diesel costs?

- Intention to change: What would you like to see happen with our company’s expansion into the Northeast?

- Recognize optimism: What makes you think that now is a good time to try something different?

- Elaboration: In what ways? Tell me more. What does that look like? (Listen for ways the supplier may be willing make a shift.)

- Favorites: “On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not at all ready to make a change and 10 is ready to make a change, where are you right now?” Note: It is rare to hear a response of 1. So, even if there is a 2 or 3 given, this provides a great opportunity to ask: “Why are you at a 2 and not a 1?” “What might happen that could move you from the 2 to a 4?” “What may happen if things continue as they are?” “If you were successful in making the changes you want, what would be different?”

-

A = Affirmations. Genuinely notice and appreciate specific strengths/actions raised in the supplier’s question responses. Procurement’s negotiator needs to recognize value by tying pros and cons together. Even if all of the elements in the supplier’s responses are not positive, take time to express authentic appreciation for the positives that their negotiator does raise. Doing this sets up collaboration and trust.

-

R = Reflections. These are statements NOT questions. They often yield more info and deeper understanding as they reinforce correct perceptions of the supplier’s responses.

- Hear what they are saying.

- Make an educated statement at their meaning and / verbalize this perception in a statement form such as: “It sounds like you are ready to reduce our pricing if we can simplify our quality inspections.” “So, you are saying that you are having trouble with the availability of copper components.” Or, “It sounds like you are feeling frustrated with our habit of placing multiple orders once monthly rather than spreading them out weekly.”

- Wait for validation. Don’t say anything else until the supplier responds. In this case, silence is golden.

- S = Summarization. Key elements of commonality can be highlighted that facilitate strategic agreement. Summarizing points of agreement helps both parties recall and reflect upon the key points. Emphasize your counterpart’s comments and views that can move them emotionally and logically to better solutions. Focus on fundamental motivations and interest.

As Marc Randolph, the founder of Netflix, once said: “Negotiation is empathy. It’s almost trite to say that if you can’t put yourself in the seat of the other person you’re speaking with, you’re not going to do well.”

The ability to understand a supplier’s psych and influence what they are thinking is key to a successful negotiation. Each of the techniques in this article can empower the phases of a productive supplier interchange. These four methods can help to alter a supplier’s perceptions in the negotiation process. We hope that they prove to be useful to the readers of this article.

SC

MR

Latest Supply Chain News

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Humanoid robots’ place in an intralogistics smart robot strategy

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- More News

Latest Resources

Explore

Explore

Business Management News

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- Supply chain salaries, job satisfaction on the rise

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- More Business Management

Latest Business Management Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks