Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

May-June 2022

I recently returned from three days in Atlanta at the Modex trade show. Although advertised as a supply chain event, it’s really a materials handling automation show with a handful of logistics providers thrown in for good measure. Heading out the door to the airport, I had no idea what to expect. The two-year absence from the trade show and conference scene had me, and many of the individuals I spoke to before the show opened, wondering what’s next—not just for the show but for operations in general. If the turnout and the enthusiasm is any indication, I think supply chain is in pretty good shape these days, despite the disruptions we’ve… Browse this issue archive.Need Help? Contact customer service 847-559-7581 More options

If there’s one word that characterizes the past two years, it is instability. Companies across the globe accustomed to predictable, stable and sustainable supply chains have been grappling with risks and disruptions that are outside the control of their organizations. It’s no surprise then that operational sustainability has emerged as a major theme for supply chain leaders, one that now incorporates supply chain stability. Afterall, innovative companies are finding ways to return to the pre-pandemic period of relative predictability. This heightened focus on identifying potential disruptors in advance of a disruption has naturally begun to encompass the portion of the supply chain that occurs outside of the enterprise itself—upstream and downstream supply chains.

Upstream includes the suppliers that create goods and services used in a company’s operations; whether as components, raw materials or ingredients that flow into “direct” manufacturing as raw materials, or the indirect products and services which facilitate the company’s actual operations. The downstream supply chain includes the partners and suppliers an organization relies on to efficiently distribute and deliver its own products or services to its customers. Whether upstream or downstream, contracted suppliers need to be proactively managed to minimize financial, confidentiality, operational, reputational and legal risks.

One of the most challenging categories of risk management has been, and continues to be, exposure to force majeure events, including events referred to as Acts of God. This article will discuss:

- the history of the term force majeure;

- what a force majeure event is;

- a typical force majeure contract clause (who it protects and the potential protections and exposures); and

- five key ways to protect your supply chain from force majeure risks.

Force majeure

The term force majeure may sound Latin, but it’s actually French. Translated correctly, it means overwhelming force.

The concept of force majeure originated in French civil law and is an accepted standard underlying many jurisdictions that derive their legal systems from the Napoleonic Code. The use of force majeure language accelerated around the globe due to World War II, when France, like many European nations, was overrun by the German army. The Germans shut down French businesses and converted many factories into the production of munitions.

After the war ended, companies whose owners had survived the war returned to their normal business operations. But the story did not end happily. Lawsuits were filed, whereby prior customers of the French companies sued them for breach of contract due to their failure to deliver product volumes during the military occupation of France. Some of the manufacturers had force majeure protections in their contracts; those without such protections were required to pay substantial damages. In some cases, owners without protections lost in court what a world war had failed to take away.

An Act of God

A force majeure event has classically been associated with an Act of God; that is an event for which no party can be held accountable. Acts of God might include natural disasters like Hurricanes Katrina or Sandy, earthquakes or flooding like that which hit Japan in 2011. But the definition also includes human actions beyond the reasonable control of a contractual party, such as war, changes to governmental policy and industry shortages. A force majeure event might also be one that is out of character for a region, such as the winter freeze in Texas in 2020. This event was so out of the ordinary in that state that many force majeure protective contract clauses kicked in for affected suppliers. Unlike in France, where force majeure is often an assumed protection in contracts, in other common law systems like those of the United States and the UK force majeure clauses are acceptable, but must be more explicit about the events that would trigger the clause.

There are exceptions. The general concept of force majeure does not apply when there is a reasonable probability of occurrence. So, if a manufacturer chooses to outsource production to a location in a politically unstable region, they may not be able to claim force majeure protections due to production failure.

Who does force majeure really protect?

In the field of procurement contracting, it is important to realize that a force majeure clause usually exists for the protection of the supplier and not the buyer. Aggressive suppliers desire this protection, and often push to carve out overly-broad aspects of relief.

But smart buying organizations can also strategically insert protections into the force majeure language to provide options in the event of an occurrence. Most important is that a buying company is not locked into exclusivity commitments without recourse regarding a non-performing supplier.

Indeed, some suppliers have overly broad force majeure protections. Early in my career, I recall the boilerplate contract language of a leading provider of copiers being excluded from performance as the result of “proximate detonation of a nuclear device.” Upon reading that, I recall thinking: “If a nuclear bomb goes off, the last thing I’m going to worry about is whether my staff can make copies.”

But, smart buyers can insist on force majeure language that protects their interests. More about that below. A typical force majeure clause might look like the example on the following page. Note that this example lists “military action or inaction” as force majeure causes. This goes back to the second world war. To this day, historians are still divided as to whether the fall of France was most attributable to German strength or French indecision. Hauntingly similar, as I’m writing this article, the Ukrainian Parliament has just voted to grant their citizens the right to carry firearms—the same day that the Russian army had already begun to invade the country. Would future force majeure claims be better attributed to military “action” or “inaction?” Time will tell. So, we see both addressed in typical force majeure language. But that’s another story.

Our clause example contains several important elements. First, it defines a force majeure event. This is critical because otherwise, too many excuses could be granted to a supplier for non-performance. Second, it establishes a notice process and protected timeline for non-performance by the party claiming the force majeure protection. Third, it establishes the right of the other party to terminate all or part of an affected contract if the allowed force majeure period exceeds a particular duration. Fourth, it permits the other party to source similar goods during the affected period, without penalty.

Without this formula, too often force majeure contract language becomes a security blanket protecting only the supplier. So, as buyers we need to carefully consider what force majeure language does and does not contain.

Force majeure

- No liability shall result to either party from delay in performance or from nonperformance caused by circumstances beyond the control of the party who has delayed performance or not performed (each, a force majeure). Such circumstances may include, but are not limited to, hurricane, flood, earthquake or other act of God, military action or inaction, or requirement of governmental authority, strike or lockout. The non-performing party shall be diligent in attempting to remove any such cause and shall promptly notify the other party of its extent and probable duration and shall give the other party such evidence as it reasonably can of such force majeure.

- If the non-performing party who has delayed performance or not performed on account of circumstances beyond its control is unable to remove the cause within 30 days of the commencement of such delay or nonperformance, the other party shall have the right to terminate the entire Agreement or any portion of it, without penalty, immediately upon written notice thereof to the non-performing party.

- Notwithstanding the foregoing, throughout any force majeure delay the other party shall have all rights to acquire similar product (or services) from an alternative provider.

Five key techniques to protect your supply chain

Let us next explore five techniques to prepare for and navigate through force majeure challenges.

Technique #1: Plan for the worst. Over several decades, experts in enterprise risk management and sustainability have realized that there are several important factors that must be considered in planning for force majeure events.

One factor is to consider the likelihood that a particular type of event may occur. If you have a supplier plant located in California, it’s wise to have a contingency plan oriented around the occurrence of an earthquake. Similarly, if your plant is near the Gulf Coast, it’s prudent to be prepared for a hurricane. These types of force majeure events have a probability that can be forecasted to some degree.

A ”black swan” event is one that cannot be statistically anticipated. Many did not consider that an event such as COVID-19 could occur—until it did. The world’s best insurance actuarial could not have forecasted 9/11. So, being prepared for “black swan” events means that a diversified strategy for dramatic change must always be in place.

Another preparation factor is to design a game plan to offset the occurrence of such an event. Consider just a few of the events we experienced in 2021 and 2022.

- Container shipments were constrained by labor issues in California ports.

- There were dramatic increases in the cost of transportation.

- Global availability of paint and resins was decimated by a winter freeze in Texas.

- War broke out in Eastern Europe.

- U.S. companies are nearshoring production to Mexico and North America due to constrained trade with China.

- Maritime passage through the Suez Canal was stopped by a grounded container ship.

- 40,000 Canadian truck drivers participated in weeks of protests.

Technique #2: Create supply chain optimization and redundancy. The most important technique to successfully transition a range of force majeure events is to design and deploy a robust supply chain. It is essential to diversify the location and capacity of your portfolio of key suppliers. There must be multiple qualified sources of supply for each important product or service needed by your operations.

For strategic sourcing diehards like me, this mean that as part of initial strategic sourcing and supplier selection, enterprise risk management (ERM) principles should be deployed to avoid over-consolidation of the supplier community. Too often, aggressive sourcing groups (and their consultants) choose to award a sole contract to a single source contractor. That works fine until a disaster occurs, such as financial failure of the supplier or a plant shutdown.

Proper strategic sourcing must select a balanced supplier portfolio to either (i) provide multiple plant or data center redundancy under the same provider (such as the ability to manufacture or perform services in multiple locations); or (ii) segment the provider relationship across multiple suppliers in a tiered primary and secondary contractual manner. Important note: Merely having a list of pre-qualified suppliers doesn’t accomplish your objective, as it can dupe you into falsely

believing you can turn to any of the alternatives during a time of need to fulfill your requirements. That mindset can lead to failure during a true force majeure event, as providers will always prioritize their most-loyal customers. They are not going to jump through hoops to support a low-volume customer that gives most of the business to their competitor during easy times.

Diversifying your supply chain will ensure that you can sustain supply chain operations even in the event of a failure in one production location.

Technique #3: Have the right force majeure contract language. It is very important for buying organizations to insist on force majeure language that protects them as much as it protects the supplier during disruptive events. The clause example earlier in this article might be a starting point to review with your legal counsel.

Key things your language should provide are as follows.

- Carefully define what really qualifies as a force majeure event. For example, when our firm was tailoring a course on strategic contracting for a large Gulf Coast energy utility client, a colleague reviewing their procurement group’s template agreements noticed something odd. The utilities’ own template contracts for emergency “right of way” vegetation clearance services along power line corridors during storm occurrences contained a generic force majeure clause that allowed non-performance “during times of inclement weather.” Their own language eliminated performance during the time when services were needed most. Our discovery of this conflict immediately resulted in 150+ contract amendments being executed with a large group of contractors to change the force majeure clause. Those amendments were completed just before the arrival of Hurricane Katrina.

- Don’t let the supplier off the hook for loss of profitability. Some suppliers want to be protected from any marketplace price changes which lessen their profits. They don’t want to bear additional costs like air freight to fulfill their customer obligations. You may be forced to accept some protections for the supplier, but a helpful principle is to protect the supplier from financial loss, but not from reduced margins (or break-even performance) during the force majeure event.

- Preserve your rights not to be affected by the supplier’s non-performance. Open the door for your company to have other options.

Having protective language in each agreement is a huge advantage for a buying company when the world turns upside-down. But rarely can we retroactively amend contracts after a force majeure event occurs in order to gain protections. The time to address this is now.

Apple’s approach is a good example. Its contract language is rumored to include a concept called, “first right of resumption.” According to sources familiar with Apple, this concept gave Apple superior rights during the devastating 2011 Tõhoku earthquake and tsunami that decimated Japanese manufacturing for months. Sources say that Apple’s protective language required many of the affected suppliers to prioritize fulfillment of Apple’s backorders before working on any other customer’s output.

Technique #4: Build the ability to monitor and manage every supplier.

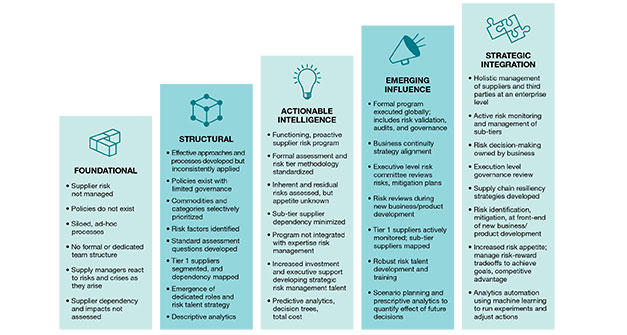

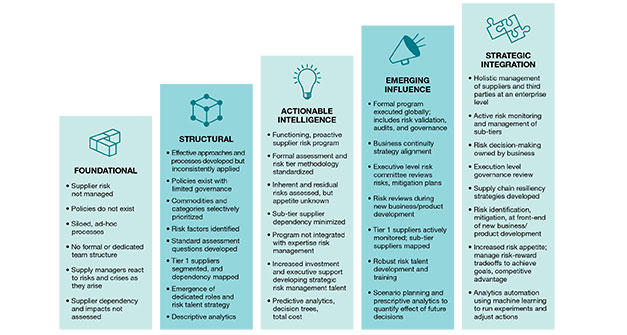

In a 2021 study, CAPS Research characterized the maturity of companies’ supplier risk management programs in the following chart. Note that in Figure 1, immature programs (on the left) tend to have limited visibility to visibility into the supply chain, while mature programs (on the right) have increasing visibility and management alignment to a buying organization’s entire portfolio of supplier risk.

When I discussed this chart with Denis Wolowiecki, executive director of CAPS Research, he said: “It is critical for less mature supply organizations to move beyond reactionary responses following the impact of a supply disruption. Top performing companies differentiate themselves by proactively identifying and managing risk in their supply chains.”

The question then is: “How can visibility, and resultant stability, be created across my portfolio of several thousand suppliers?” The good news is that this no longer requires excessive staff build-ups or costly subscriptions to external providers of supplier risk data. Dramatic change is coming to the supplier risk space similar to the entrance of Amazon, Uber or DoorDash in their respective industries. Interestingly, one of the largest and fastest-growing supplier risk management companies neither advertises nor participates in technology solution reviews*. At no cost to a corporate customer, this provider performs the following types of risk management services for every supplier:

- verification of supplier taxpayer registration;

- predictive financial stability tracking (active monitoring and notification);

- digital validation of supplier insurance policy coverage(s);

- checking of supplier against 1,500 governmental watchlists (terrorism, rare earth minerals, environmental, restricted country/provinces, labor law violations, child labor practices, slave labor, human trafficking, etc.);

- cybersecurity review of supplier website exposure;

- monitoring of legal judgements and liens against each supplier; and

- monitoring of 30,000 global media sources for negative news accounts about the supplier (often force majeure related).

Technique #5: Proactively manage key supplier relationships. Once you have a foundation that provides insight and monitoring of every supplier’s risk exposure, a proven method of risk avoidance is to Pareto all supplier portfolio companies into categories based on financial spend or assigned risk using techniques. For example:

- Class A suppliers (the 15% of suppliers representing 75% of total spend);

- Class B suppliers (the 25% of suppliers representing 15% of total spend); and

- Class C suppliers (the 60% of suppliers representing 10% of total spend).

Using these types of categorizations, strategy coaching and feedback can be developed. This should address strategic preparations to manage through force majeure events but can also dovetail nicely with overall supplier performance. Often Class A and some Class B providers are met within a parent/teacher/student coaching model to identify improvement opportunities and corrective actions for deficient

performance. Class C suppliers are rated and moved up or out based on their ability to meet objective objectives regarding risk preparation and performance. Using data from your supplier risk solution* and ERP or MRP technology tool, also consider tracking all suppliers’ performance and risk exposure and notifying the supplier of needed improvement.

Figure One: Supplier risk management maturity model

Supplier Risk Management Maturity Model, CAPS Research & Arizona State University, 2021

By now, it should be clear that it’s imperative to proactively manage supplier risk. This is especially true with regards to force majeure events. Using these five techniques can prepare any organization to navigate through force majeure events as well as disruptive occurrences that seem to be part of the new normal.

Astronaut Jim Lovell once said: “There are people who make things happen, there are people who watch things happen and there are people who wonder what happened.” The same is true regarding force majeure supply chain events if we’re not prepared.

SC

MR

Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

May-June 2022

I recently returned from three days in Atlanta at the Modex trade show. Although advertised as a supply chain event, it’s really a materials handling automation show with a handful of logistics providers thrown in… Browse this issue archive. Access your online digital edition. Download a PDF file of the May-June 2022 issue.If there’s one word that characterizes the past two years, it is instability. Companies across the globe accustomed to predictable, stable and sustainable supply chains have been grappling with risks and disruptions that are outside the control of their organizations. It’s no surprise then that operational sustainability has emerged as a major theme for supply chain leaders, one that now incorporates supply chain stability. Afterall, innovative companies are finding ways to return to the pre-pandemic period of relative predictability. This heightened focus on identifying potential disruptors in advance of a disruption has naturally begun to encompass the portion of the supply chain that occurs outside of the enterprise itself—upstream and downstream supply chains.

Upstream includes the suppliers that create goods and services used in a company’s operations; whether as components, raw materials or ingredients that flow into “direct” manufacturing as raw materials, or the indirect products and services which facilitate the company’s actual operations. The downstream supply chain includes the partners and suppliers an organization relies on to efficiently distribute and deliver its own products or services to its customers. Whether upstream or downstream, contracted suppliers need to be proactively managed to minimize financial, confidentiality, operational, reputational and legal risks.

One of the most challenging categories of risk management has been, and continues to be, exposure to force majeure events, including events referred to as Acts of God. This article will discuss:

- the history of the term force majeure;

- what a force majeure event is;

- a typical force majeure contract clause (who it protects and the potential protections and exposures); and

- five key ways to protect your supply chain from force majeure risks.

Force majeure

The term force majeure may sound Latin, but it’s actually French. Translated correctly, it means overwhelming force.

The concept of force majeure originated in French civil law and is an accepted standard underlying many jurisdictions that derive their legal systems from the Napoleonic Code. The use of force majeure language accelerated around the globe due to World War II, when France, like many European nations, was overrun by the German army. The Germans shut down French businesses and converted many factories into the production of munitions.

After the war ended, companies whose owners had survived the war returned to their normal business operations. But the story did not end happily. Lawsuits were filed, whereby prior customers of the French companies sued them for breach of contract due to their failure to deliver product volumes during the military occupation of France. Some of the manufacturers had force majeure protections in their contracts; those without such protections were required to pay substantial damages. In some cases, owners without protections lost in court what a world war had failed to take away.

An Act of God

A force majeure event has classically been associated with an Act of God; that is an event for which no party can be held accountable. Acts of God might include natural disasters like Hurricanes Katrina or Sandy, earthquakes or flooding like that which hit Japan in 2011. But the definition also includes human actions beyond the reasonable control of a contractual party, such as war, changes to governmental policy and industry shortages. A force majeure event might also be one that is out of character for a region, such as the winter freeze in Texas in 2020. This event was so out of the ordinary in that state that many force majeure protective contract clauses kicked in for affected suppliers. Unlike in France, where force majeure is often an assumed protection in contracts, in other common law systems like those of the United States and the UK force majeure clauses are acceptable, but must be more explicit about the events that would trigger the clause.

There are exceptions. The general concept of force majeure does not apply when there is a reasonable probability of occurrence. So, if a manufacturer chooses to outsource production to a location in a politically unstable region, they may not be able to claim force majeure protections due to production failure.

Who does force majeure really protect?

In the field of procurement contracting, it is important to realize that a force majeure clause usually exists for the protection of the supplier and not the buyer. Aggressive suppliers desire this protection, and often push to carve out overly-broad aspects of relief.

But smart buying organizations can also strategically insert protections into the force majeure language to provide options in the event of an occurrence. Most important is that a buying company is not locked into exclusivity commitments without recourse regarding a non-performing supplier.

Indeed, some suppliers have overly broad force majeure protections. Early in my career, I recall the boilerplate contract language of a leading provider of copiers being excluded from performance as the result of “proximate detonation of a nuclear device.” Upon reading that, I recall thinking: “If a nuclear bomb goes off, the last thing I’m going to worry about is whether my staff can make copies.”

But, smart buyers can insist on force majeure language that protects their interests. More about that below. A typical force majeure clause might look like the example on the following page. Note that this example lists “military action or inaction” as force majeure causes. This goes back to the second world war. To this day, historians are still divided as to whether the fall of France was most attributable to German strength or French indecision. Hauntingly similar, as I’m writing this article, the Ukrainian Parliament has just voted to grant their citizens the right to carry firearms—the same day that the Russian army had already begun to invade the country. Would future force majeure claims be better attributed to military “action” or “inaction?” Time will tell. So, we see both addressed in typical force majeure language. But that’s another story.

Our clause example contains several important elements. First, it defines a force majeure event. This is critical because otherwise, too many excuses could be granted to a supplier for non-performance. Second, it establishes a notice process and protected timeline for non-performance by the party claiming the force majeure protection. Third, it establishes the right of the other party to terminate all or part of an affected contract if the allowed force majeure period exceeds a particular duration. Fourth, it permits the other party to source similar goods during the affected period, without penalty.

Without this formula, too often force majeure contract language becomes a security blanket protecting only the supplier. So, as buyers we need to carefully consider what force majeure language does and does not contain.

Force majeure

- No liability shall result to either party from delay in performance or from nonperformance caused by circumstances beyond the control of the party who has delayed performance or not performed (each, a force majeure). Such circumstances may include, but are not limited to, hurricane, flood, earthquake or other act of God, military action or inaction, or requirement of governmental authority, strike or lockout. The non-performing party shall be diligent in attempting to remove any such cause and shall promptly notify the other party of its extent and probable duration and shall give the other party such evidence as it reasonably can of such force majeure.

- If the non-performing party who has delayed performance or not performed on account of circumstances beyond its control is unable to remove the cause within 30 days of the commencement of such delay or nonperformance, the other party shall have the right to terminate the entire Agreement or any portion of it, without penalty, immediately upon written notice thereof to the non-performing party.

- Notwithstanding the foregoing, throughout any force majeure delay the other party shall have all rights to acquire similar product (or services) from an alternative provider.

Five key techniques to protect your supply chain

Let us next explore five techniques to prepare for and navigate through force majeure challenges.

Technique #1: Plan for the worst. Over several decades, experts in enterprise risk management and sustainability have realized that there are several important factors that must be considered in planning for force majeure events.

One factor is to consider the likelihood that a particular type of event may occur. If you have a supplier plant located in California, it’s wise to have a contingency plan oriented around the occurrence of an earthquake. Similarly, if your plant is near the Gulf Coast, it’s prudent to be prepared for a hurricane. These types of force majeure events have a probability that can be forecasted to some degree.

A ”black swan” event is one that cannot be statistically anticipated. Many did not consider that an event such as COVID-19 could occur—until it did. The world’s best insurance actuarial could not have forecasted 9/11. So, being prepared for “black swan” events means that a diversified strategy for dramatic change must always be in place.

Another preparation factor is to design a game plan to offset the occurrence of such an event. Consider just a few of the events we experienced in 2021 and 2022.

- Container shipments were constrained by labor issues in California ports.

- There were dramatic increases in the cost of transportation.

- Global availability of paint and resins was decimated by a winter freeze in Texas.

- War broke out in Eastern Europe.

- U.S. companies are nearshoring production to Mexico and North America due to constrained trade with China.

- Maritime passage through the Suez Canal was stopped by a grounded container ship.

- 40,000 Canadian truck drivers participated in weeks of protests.

Technique #2: Create supply chain optimization and redundancy. The most important technique to successfully transition a range of force majeure events is to design and deploy a robust supply chain. It is essential to diversify the location and capacity of your portfolio of key suppliers. There must be multiple qualified sources of supply for each important product or service needed by your operations.

For strategic sourcing diehards like me, this mean that as part of initial strategic sourcing and supplier selection, enterprise risk management (ERM) principles should be deployed to avoid over-consolidation of the supplier community. Too often, aggressive sourcing groups (and their consultants) choose to award a sole contract to a single source contractor. That works fine until a disaster occurs, such as financial failure of the supplier or a plant shutdown.

Proper strategic sourcing must select a balanced supplier portfolio to either (i) provide multiple plant or data center redundancy under the same provider (such as the ability to manufacture or perform services in multiple locations); or (ii) segment the provider relationship across multiple suppliers in a tiered primary and secondary contractual manner. Important note: Merely having a list of pre-qualified suppliers doesn’t accomplish your objective, as it can dupe you into falsely

believing you can turn to any of the alternatives during a time of need to fulfill your requirements. That mindset can lead to failure during a true force majeure event, as providers will always prioritize their most-loyal customers. They are not going to jump through hoops to support a low-volume customer that gives most of the business to their competitor during easy times.

Diversifying your supply chain will ensure that you can sustain supply chain operations even in the event of a failure in one production location.

Technique #3: Have the right force majeure contract language. It is very important for buying organizations to insist on force majeure language that protects them as much as it protects the supplier during disruptive events. The clause example earlier in this article might be a starting point to review with your legal counsel.

Key things your language should provide are as follows.

- Carefully define what really qualifies as a force majeure event. For example, when our firm was tailoring a course on strategic contracting for a large Gulf Coast energy utility client, a colleague reviewing their procurement group’s template agreements noticed something odd. The utilities’ own template contracts for emergency “right of way” vegetation clearance services along power line corridors during storm occurrences contained a generic force majeure clause that allowed non-performance “during times of inclement weather.” Their own language eliminated performance during the time when services were needed most. Our discovery of this conflict immediately resulted in 150+ contract amendments being executed with a large group of contractors to change the force majeure clause. Those amendments were completed just before the arrival of Hurricane Katrina.

- Don’t let the supplier off the hook for loss of profitability. Some suppliers want to be protected from any marketplace price changes which lessen their profits. They don’t want to bear additional costs like air freight to fulfill their customer obligations. You may be forced to accept some protections for the supplier, but a helpful principle is to protect the supplier from financial loss, but not from reduced margins (or break-even performance) during the force majeure event.

- Preserve your rights not to be affected by the supplier’s non-performance. Open the door for your company to have other options.

Having protective language in each agreement is a huge advantage for a buying company when the world turns upside-down. But rarely can we retroactively amend contracts after a force majeure event occurs in order to gain protections. The time to address this is now.

Apple’s approach is a good example. Its contract language is rumored to include a concept called, “first right of resumption.” According to sources familiar with Apple, this concept gave Apple superior rights during the devastating 2011 Tõhoku earthquake and tsunami that decimated Japanese manufacturing for months. Sources say that Apple’s protective language required many of the affected suppliers to prioritize fulfillment of Apple’s backorders before working on any other customer’s output.

Technique #4: Build the ability to monitor and manage every supplier.

In a 2021 study, CAPS Research characterized the maturity of companies’ supplier risk management programs in the following chart. Note that in Figure 1, immature programs (on the left) tend to have limited visibility to visibility into the supply chain, while mature programs (on the right) have increasing visibility and management alignment to a buying organization’s entire portfolio of supplier risk.

When I discussed this chart with Denis Wolowiecki, executive director of CAPS Research, he said: “It is critical for less mature supply organizations to move beyond reactionary responses following the impact of a supply disruption. Top performing companies differentiate themselves by proactively identifying and managing risk in their supply chains.”

The question then is: “How can visibility, and resultant stability, be created across my portfolio of several thousand suppliers?” The good news is that this no longer requires excessive staff build-ups or costly subscriptions to external providers of supplier risk data. Dramatic change is coming to the supplier risk space similar to the entrance of Amazon, Uber or DoorDash in their respective industries. Interestingly, one of the largest and fastest-growing supplier risk management companies neither advertises nor participates in technology solution reviews*. At no cost to a corporate customer, this provider performs the following types of risk management services for every supplier:

- verification of supplier taxpayer registration;

- predictive financial stability tracking (active monitoring and notification);

- digital validation of supplier insurance policy coverage(s);

- checking of supplier against 1,500 governmental watchlists (terrorism, rare earth minerals, environmental, restricted country/provinces, labor law violations, child labor practices, slave labor, human trafficking, etc.);

- cybersecurity review of supplier website exposure;

- monitoring of legal judgements and liens against each supplier; and

- monitoring of 30,000 global media sources for negative news accounts about the supplier (often force majeure related).

Technique #5: Proactively manage key supplier relationships. Once you have a foundation that provides insight and monitoring of every supplier’s risk exposure, a proven method of risk avoidance is to Pareto all supplier portfolio companies into categories based on financial spend or assigned risk using techniques. For example:

- Class A suppliers (the 15% of suppliers representing 75% of total spend);

- Class B suppliers (the 25% of suppliers representing 15% of total spend); and

- Class C suppliers (the 60% of suppliers representing 10% of total spend).

Using these types of categorizations, strategy coaching and feedback can be developed. This should address strategic preparations to manage through force majeure events but can also dovetail nicely with overall supplier performance. Often Class A and some Class B providers are met within a parent/teacher/student coaching model to identify improvement opportunities and corrective actions for deficient

performance. Class C suppliers are rated and moved up or out based on their ability to meet objective objectives regarding risk preparation and performance. Using data from your supplier risk solution* and ERP or MRP technology tool, also consider tracking all suppliers’ performance and risk exposure and notifying the supplier of needed improvement.

Figure One: Supplier risk management maturity model

Supplier Risk Management Maturity Model, CAPS Research & Arizona State University, 2021

By now, it should be clear that it’s imperative to proactively manage supplier risk. This is especially true with regards to force majeure events. Using these five techniques can prepare any organization to navigate through force majeure events as well as disruptive occurrences that seem to be part of the new normal.

Astronaut Jim Lovell once said: “There are people who make things happen, there are people who watch things happen and there are people who wonder what happened.” The same is true regarding force majeure supply chain events if we’re not prepared.

SC

MR

More Risk Management

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- Shining light on procurement’s dark purchases problem

- More Risk Management

Latest Podcast

Explore

Explore

Procurement & Sourcing News

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- Shining light on procurement’s dark purchases problem

- More Procurement & Sourcing

Latest Procurement & Sourcing Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks