Industry analysts agree that it’s important to make risk assessment an ongoing process, allowing for frequent plan updates as political conditions, fuel prices, tariffs, currency exchange rates, labor costs, and other supply chain security threats arise. Up until now, the focus for most US manufacturers has been on protecting its most asset-intensive suppliers, to ensure that key high-value components are always available.

But a new body of research on supply-chain risk suggests there may be no correlation between the total amount a manufacturer spends with a supplier and the profit loss it would incur if that supply were suddenly interrupted.

This “counterintuitive” finding by MIT scholars and analysts defies a basic business tenet that equates the greatest supply-chain risk with suppliers of highest annual expenditure.

When applied to Ford Motor Company’s supply chain, the quantitative analysis by Professor David Simchi-Levi of MIT’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Division shows that the supply firms whose disruption would inflict the greatest blow to Ford’s profits are those that provide the manufacturer with relatively low-cost components.

“This helps explain why risk in a complex supply network often remains hidden,” says Simchi-Levi, who is co-director of MIT’s Leaders for Global Operations program. “The risk occurs in unexpected locations and components of a manufacturer’s supply network.”

A paper on the application of this work to Ford’s supply chain by Simchi-Levi and former graduate students William Schmidt, now an assistant professor at Cornell University, and Yehua Wei, an assistant professor at Duke University, will appear in the January/February issue of Harvard Business Review.

Focus on Low-probability, High-impact risk

Traditional methods for identifying the suppliers and events that pose the highest risk depend on knowing the probability that a specific type of risk event will occur at any firm and knowing the magnitude of the problems that would ensue. However, risks — which can range from a brief work stoppage to a major natural disaster — exist on a continuum of frequency and predictability, and the sources of low-probability, high-impact risk are difficult to quantify. Manufacturers generally assume their greatest supply-chain risk is tied to suppliers of highest expenditure.

But Simchi-Levi reasoned that because a company’s mitigation choices — maintaining more inventory or an alternative supply source, for example — are the same regardless of the type of problem that occurs, a mathematical model of supply-chain risk should determine the impact to the company’s operations if any disruption occurs, rather than estimating the probability of specific types of risks.

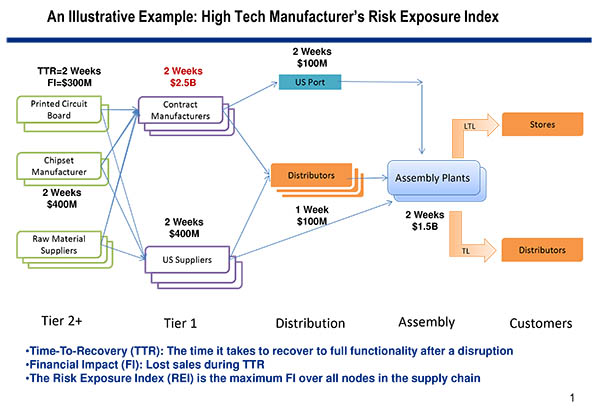

His model incorporates bill-of-material information (the list of ingredients required to build a company’s products); maps each part or material to one or more of the firm’s facilities and product lines; captures multiple tiers of supplier relationships (tier 1 are direct suppliers, tier 2 are suppliers to tier 1 firms, and so on); includes operational and financial impact measures; and incorporates supplier recovery time if a problem occurs.

As nodes are removed one at a time from the supply network, the model determines how best to reallocate inventory and obtain alternatives, and predicts financial impact. The resulting analysis divides suppliers into three segments depending on the cost of the individual components they provide and the financial impact their shortage would have: low-cost components/high financial impact; high-cost components/high financial impact; and low-cost components/low financial impact.

Highest Risk From 2 Percent of Suppliers

When Simchi-Levi, Schmidt, and Wei applied the model to Ford’s multitier supply network — which has long lead times from some providers, a complex bill-of-materials structure, components that are shared across multiple product lines, and thousands of components from tier 1 suppliers — the model predicted that a short disruption at 61 percent of the tier 1 firms would not cause profit loss. By contrast, a halt in distribution from about 2 percent of firms would have a very large impact on Ford’s profits. Yet each of those firms in the 2 percent furnishes Ford with less-expensive components rather than, say, expensive car seats and instrument panels that fall into the high-financial-impact segment.

“The ability to manage and respond to supply-chain disruptions is becoming one of the critical success factors of executives,” says Hau Lee, a professor of operations, information, and technology at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, who was not involved in the study. “Addressing low-probability disruptions has often been viewed as black magic, as standard quantitative methods simply do not work. The authors have come up with an innovative, structured approach, so that executives could use a rational decision process to gain control of this problem.”

The relevance of this methodology can be seen in light of a disruption in 2012 at a plant in Europe, which caused a shortage of a polymer used by most manufacturer-suppliers to make fuel tanks, brake components, and seat fabrics. It took six months to restart production, a delay that had a large financial impact on the auto industry. Simchi-Levi’s framework would have encouraged the company to build a second plant in a different region, something the affected company now is doing in Asia.

Keeping Track of Supplier Solvency

Creating back up plans and due diligence reports for smaller suppliers should also be a priority says Rose Kelly-Falls, senior vice president, Supply Chain Risk Management at Rapid Ratings International, in Indianapolis, Indiana. She posed this rhetorical question to shippers last year: Are supply chain managers paying proper attention to their supplier’s solvency?

From her point of view, the answer is a resounding NO.

“Solvency is the degree to which current assets exceed liabilities,” she explains. “If supply chain managers miss any ‘red flags’ in this area, they do so at their own peril,”

Kelly-Falls likes to tell a story about a small private machining company that was a second-tier supplier of clutch gears for a major U.S. auto manufacturer. It was located in a remote community, and was quietly purchased by a toy manufacturer without much fanfare. “So when the auto maker needed a crucial piece of equipment for a new product launch, it was suddenly unavailable,” she recalls. “Why? Because this big multinational corporation did not ever bother keeping track of what it perceived to be a minor business partner.” The result, she recalls, was a missed deadline and the loss of millions of dollars in revenue. Had the relationship not been underestimated, the risk could have been mitigated.

More than ever before, says Kelly-Falls, logistics managers need to understand their private suppliers, and carefully monitor their financial condition. “This is crucial for a number of reasons,” she says “Typically, they lower tier suppliers 70-80% of a manufacturer’s company’s supply base. Many of their issues are not uncovered or realized until they are out of control. Furthermore, she says, sub-tier private suppliers often don’t have the resources to develop and implement a risk management strategy of their own.

“Smaller private companies may have loose governance and have less access to capital to invest in programs or projects. In fact, many tend to lean on their customer to provide financial support.”

Related Content on Supply Chain 24/7: Hidden Risk in Supply Chains

SC

MR

Latest Supply Chain News

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Humanoid robots’ place in an intralogistics smart robot strategy

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- More News

Latest Podcast

Explore

Explore

Topics

Latest Supply Chain News

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Humanoid robots’ place in an intralogistics smart robot strategy

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- More latest news

Latest Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks