Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

November 2020

Supply chains have been in the spotlight like never before over the last eight months. That hasn’t always been a good thing. The perception, reinforced by shortages of products essential to our daily lives, is that supply chains were not up to the task and failed. The reality, as argued by MIT’s Yossi Sheffi in his new book, “The New (Ab)Normal: Reshaping Business and Supply Chain Strategy Beyond COVID-19,” is that supply chains performed as designed—they did what we expected them to do. Browse this issue archive.Need Help? Contact customer service 847-559-7581 More options

To say that these are uncertain times is an understatement. It can be argued that there haven’t been such across the board supply chain disruptions since the end of World War II. For starters, businesses face changes in demand. Unemployment remains elevated while business sentiment on future hires continues to be pessimistic; although recent weeks have seen an abatement in the unemployment rate, future layoffs in industries such as commercial aviation and the oil industry seem inevitable.

These labor market disruptions have taken a significant toll on consumer spending, which declined sharply in the first half of the year and is expected to remain weak for the foreseeable future. Consumers have also changed their spending habits, disrupting traditional revenue streams in a number of industries. And though opportunities exist, many companies aren’t well positioned to take advantage of shifting customer requirements.

Demand disruptions have been exacerbated by supply disruptions. Companies entered 2020 with their supply chains already battered by the ongoing U.S.-China trade war. The pandemic worsened these problems by shutting down key partners, scrambling production and delivery schedules.

Global production, particularly in China, dropped sharply earlier this year and will take time to recover. Meanwhile, distribution networks continue to struggle with shifts in demand, further exposing weaknesses in the supply chain. As companies work to adjust, they are re-learning the lesson that dependable supply chain relationships take time and resources to develop.

Finally, businesses may be facing a slow-burning credit shock. Despite unprecedented moves by the federal reserve, debt laden corporations continue to face pressure. Downgrades of corporate bonds to sub-investment status are on track to reach all-time highs. Moreover, the use of leveraged loans and other practices reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis have reduced transparency and increased the broader economy’s exposure to potentially risky debt. The longer supply and demand problems squeeze profits, the more likely defaults will occur.

And all of these challenges sit on top of a highly charged social and political environment rocked by racial unrest, a resurgence of the COVID-19 virus and an election. It is no wonder that the Atlanta Fed’s Survey of Business Uncertainty has been at historically high levels for most of the year.

The three Ps

Despite headwinds, businesses still expect supply chain managers to find a way through this minefield while continuing to deliver value to customers at a profit. New research by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Global Supply Chain Institute highlights end-to-end supply chain synchronization as a leading-edge strategy that companies can use to manage shocks, recover stability and set the stage for future gains (See About our research).

Supply chain synchronization focuses on building supply chain capabilities and linking them to a core business driver to create a platform for long-term organizational success. It requires a deep understanding of the core business driver and the creation of a supply chain where physical assets, business processes and people systems (the Three Ps of Supply Chain Synchronization) are intimately linked to its strategic imperatives. Table 1 provides guidance on how companies can manage the Three Ps to develop a synchronized supply chain.

As an example, a global paper manufacturer recently undertook a comprehensive analysis of its manufacturing operations. The analysis revealed that, while some categories rested on operations designed to maximize capacity utilization, other categories rested on operations designed to meet demand at scale. Overall, however, supply chain activities were not clearly or directly tied to meeting specific consumer requirements, which was identified as the company’s core business driver. Through a process of supply chain synchronization, the company was able to realign its supply chain across all categories to drive the business to operate from a more consumer-centric point of view. Flexible equipment, changeover time reduction and agile teams are now the foundation of the company’s operations. These changes have allowed the company to maintain its performance in the current environment.

This type of total supply chain transformation remains rare. Despite improving performance within different areas that comprise the end-to-end supply chain, many supply chain leaders acknowledge that their efforts are often out of sync with the goals and directions of the overall business. In most organizations, strategy discussions usually make only a superficial impact on supply chain operations. Supply chain leaders, to the extent that they are involved in these discussions, are often relegated to supporting roles. And what comes out of strategy discussions often lacks clear guidelines for how the supply chain needs to be managed. As a result, supply chain managers fall back on implementing “popular” supply chain strategies or “optimizing” supply chain processes without understanding the core business driver toward which the supply chain must ultimately be aligned.

As Steve Bowen, CEO of the global supply chain consulting firm Maine Pointe and participant in the research, put it: “The core business driver sets the parameters for business decision-making and has an impact on how resources are allocated throughout the supply chain and operations. Executives and supply chain leaders need to have a clear understanding of the driver and continuously align operations to meet its requirements. Ultimately, they need to build supply chains that deliver total value optimization—support company goals on cost, cash flows and growth.”

Best practices

A handful of leading organizations are working to synchronize supply chain operations with their core business driver in order to unlock the full potential of the supply chain as a source of competitive advantage. In order to better understand what these companies are doing, researchers acting as part of the UT research team conducted in-depth field interviews with 13 benchmark companies spanning food, equipment, furniture, chemical, packaging, health care and CPG industries. The interviews yielded six best practices that companies can follow to more closely synchronize their supply chains.

1. Alignment with the core business driver

Alignment with the core business driver is what makes the synchronization strategy unique. Historically, supply chains have simply tracked continuous improvement on a range of activities without a clear understanding of how (or whether) these activities related to the core business driver. The companies interviewed for this research, by contrast, found that significant waste can accrue when supply chain operations are managed using a narrowly focused “improvement” lens. These companies found that financial metrics were far better at aligning operations to the business driver. They emphasized that all functions needed to actively participate in providing data, experience and knowledge from an end-to-end perspective. Critical areas of understanding that needed to be communicated included a detailed analysis of cost of goods sold (COGS), customer service requirements and areas of waste generation. Finally, while recognizing that a company might operate multiple supply chains and have multiple business drivers, leading companies emphasized the need for every supply chain to focus on a single business driver. If more than one business driver was identified, supply chain leaders placed the most important driver as the centerpiece of their synchronization strategy.

2. Multifunctional leadership

The synchronization best practice mentioned most frequently in interviews was the need for strong multifunctional leadership. This best practice is not unique to synchronization, but is absolutely critical for the success of a synchronization effort. In the face of extraordinary levels of uncertainty, the greatest opportunities for value creation come from managing the seams and intersections of complex value chains. The days of simply running an efficient supply chain are over. Top supply chain executives must have excellent boundary management skills, and the ability to influence both commercial and financial leaders, to succeed in this environment. At the same time, supply chain leaders need to assemble multi-functional teams and task them with identifying initiatives for simplifying and synchronizing workflows across the organization. Teams should include representatives from sales, finance and product research—as well as traditional supply chain functions—and focus on enhancing business processes with an eye toward improving key financial metrics.

3. Value stream mapping

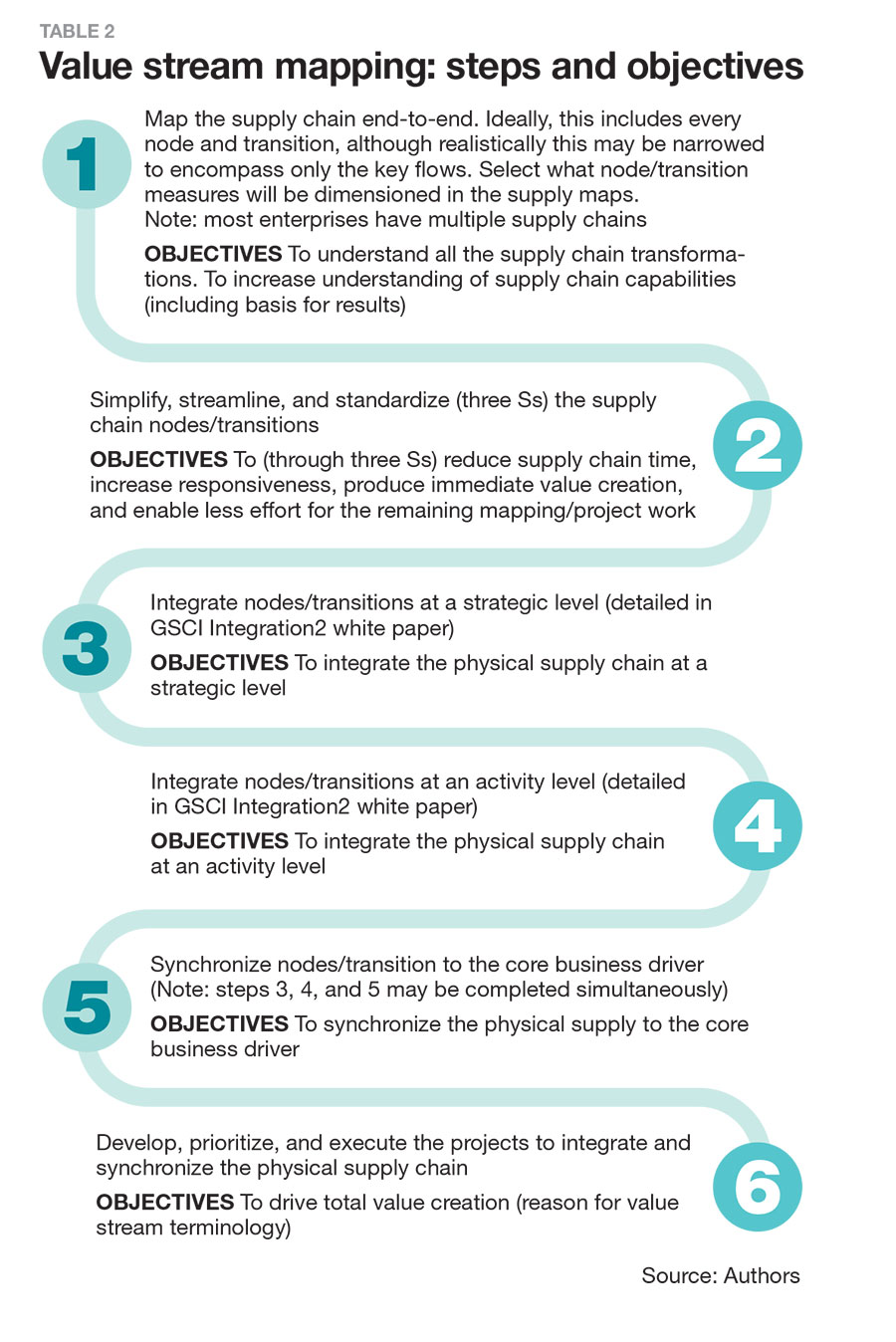

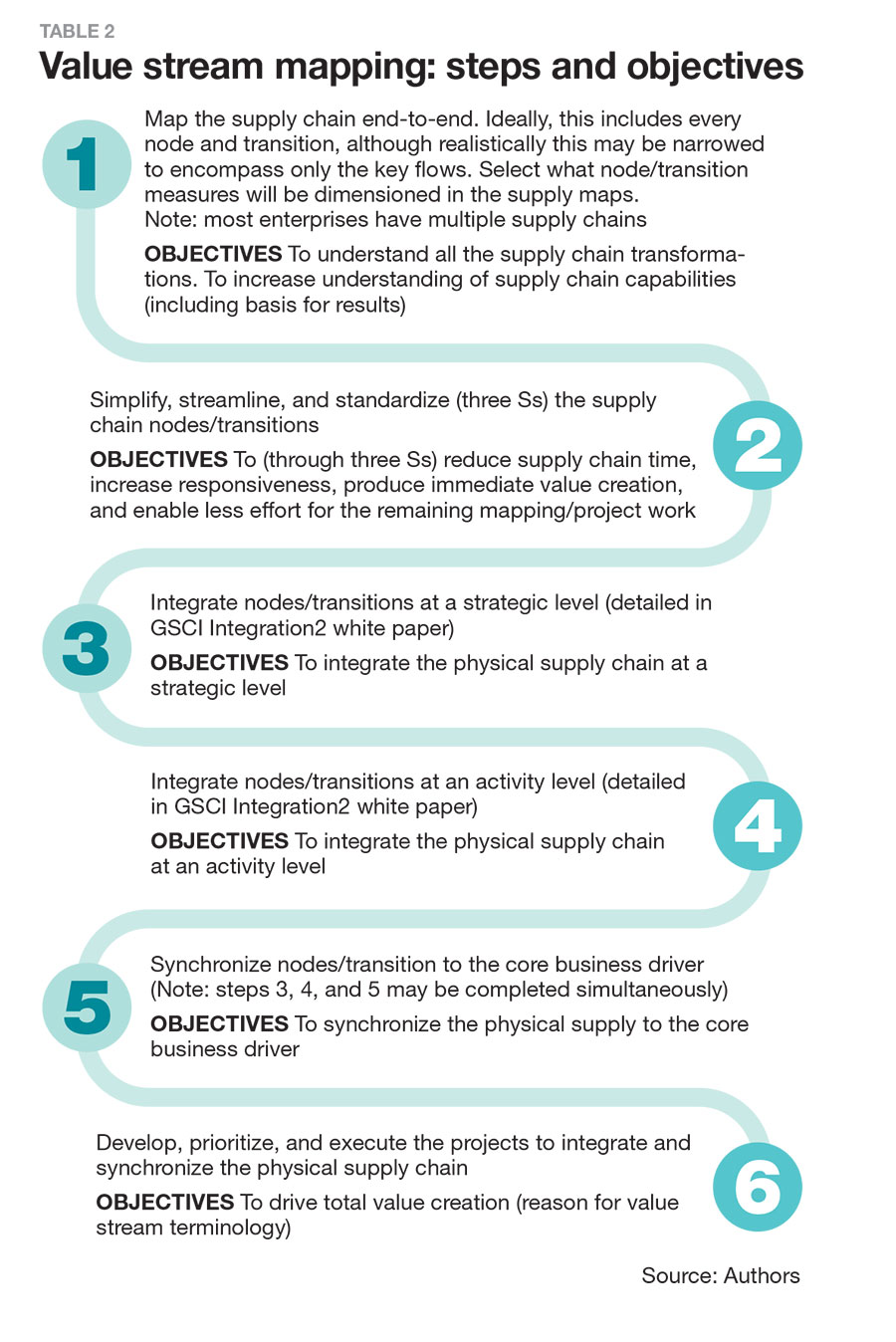

Leading companies emphasized value stream mapping as perhaps the most important tool for executing a synchronization strategy. Three major points in particular were emphasized. First, companies needed to define the value stream broadly. For leading companies, the value stream included everything required for an enterprise to deliver value creation. This included design, source, make, deliver, sell and service. Second, the purpose of the value stream was to deliver the end business objective. Leading companies used the term value stream to focus the organization on the purpose of the system. The goal was to visualize where every part of the supply chain fit into the value stream, so that the entire organization would be fully involved in managing and improving the value stream. Third, value stream mapping was detailed work and the total effort required to map a value stream for a large, global, multi-category business was significant. Teams could lose sight of the objective and get caught up in the grind of mapping the system. Labeling the work as value stream mapping reinforced the critical point that the purpose is to increase total value.

Mapping exercises generate hundreds of questions regarding supply base management, process redundancy and integration, customer fulfillment and more. Building on the value stream map, leading companies first focused on simplifying their supply chains, then standardizing and integrating processes, and only lastly did they move toward implementing a synchronization strategy. In this way, teams were able to achieve tangible, incremental benefits while building the necessary skills and relationships needed to tackle the ambitious end goal of synchronization. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the process.

4. Dependable supply chain operations

To achieve dependable supply chain operations, leading companies focused on two key aspects. First, they advanced common values across the supply chain. Common values help these companies prevent significant conflicts within and between organizations. They allow management to focus on value creation as opposed to dispute settlement. Common values are especially important in the current environment, where uncertainty can break contracts—and relationships—without collective commitment to value creation goals.

Second, leading companies focused on creating reliable, predictable, zero waste supply chains. A typical supply chain incorporates thousands of activities and transformations. This system is only as reliable and predictable as its weakest link. Importantly, leading companies recognized that a high level of reliability does not guarantee a predictable outcome. For instance, a supply chain with 100 dependent steps, where each step delivered its product on time 98% of the time, would achieve less than 20% on-time delivery of product. Supply chains need to be both reliable and predictable. Reliable and predictable operations enable leadership to work on more strategic capabilities. Conversely, non-reliable or unpredictable supply chains require attention on managing day-to-day issues.

Zero waste directly supports the work of creating a reliable and predictable supply chain. The highest levels of waste are typically observed in areas where people and processes intersect, including product design, integration across units, information exchange and coordination with suppliers and customers. Rooting out waste in these areas produced more effective interactions, leading to better reliability and predictability.

5. End-to-end, digitally enabled visibility

Supply chain visibility played a critical role in synchronization strategies at leading companies. These companies operated on the motto “you can’t fix what you can’t see.” Hence these companies invested significantly in technologies that provided visibility into the end-to-end supply chain. Digitalization of the supply chain has advanced dramatically over the last decade, enabling integrated, platform-based supply chains.

Leading companies have applied these technologies to their synchronization efforts. For instance, companies have used digital technologies to capture massive amounts of data and apply real-time analysis to track traditional variables—such as cost, quality and delivery—as well as agility-based variables—such as time, cash, service and responsiveness. In one example, a heavy equipment manufacturer implemented digital information systems to view its entire global inventory system. Inventory is now visible in manufacturing warehouses, transit, replenishment centers and franchises. This capability has enabled the company to enact inventory sharing processes to increase service while reducing cash outlays.

In addition, leading companies used analytical tools to model the supply chain, simulate solutions and continuously improve systems to deliver optimized total value (service, time, cost, revenue, quality, cash). This capability has become the basis for improved end-to-end planning and replenishment systems using internal and external data to improve how the supply chain is managed.

6. Develop skills and capabilities to execute synchronization

Finally, synchronization requires supply chain personnel to develop new skills and capabilities. Leading companies highlighted some of the most important skills for executing a synchronization strategy. These include the ability to influence others (particularly in areas outside their expertise), multi-functional business process skills and experiences, boundary management, financial literacy, and business analytics and other digital capabilities.

Companies can take numerous approaches to developing the skills and capabilities needed to execute synchronization. One company interviewed by the research team developed a global community of practice (CoP) approach to document and promote key capabilities. Successful work processes were developed, standardized and validated. These processes were then captured by the CoP for training and reapplication. The organization is focused on keeping the CoP alive and current to address the challenges of efficiently managing complex global operations. Other approaches exist as well.

Regardless of the approach, the key takeaway from interviews was the need to shift away from a limited focus on functional skills to a broader focus on talent development. Companies also emphasized the need to find, hire, develop and retain talent as critical to synchronization.

Emerging synchronization strategies

Leading companies are applying these best practices to ensure that all supply chain assets, processes and people are synchronized to the core business driver. An omni-channel retailer, for instance, was struggling before the current crisis to respond to rapidly changing consumer behavior and the threat of disruptive business models. The company first identified internet consumer orders with low average demand and high variation as its core business driver. In order to synchronize its supply chain to these customers, it implemented market leading data analytics that enabled visibility, improved control and optimized inventory levels. The company also streamlined operations to enhance dependability in its end-to-end supply chain. As a result, it was able to decrease working capital by 25%, reduce logistics spend by up to 12% and save tens of millions of dollars in procurement costs.

Not all companies that were interviewed achieved such striking success. Because synchronization is still a very new strategy, many leading companies had yet to achieve full implementation. Other companies were building on partial successes to achieve greater gains. But all of the companies were convinced the synchronization was critical to the long-term growth of their companies.

Most importantly, perhaps, synchronization can help companies weather the challenges and opportunities of economic uncertainty. When shocks occur, end-to-end visibility—coupled with strong relationships—provide a critical foundation for maintaining operations. At the same time, having a clear understanding of the core business driver gives companies critical direction in deciding how best to adjust to new circumstances. In many cases, this means precisely defining the customers or segments whose value requirements best align with the company’s capabilities and are the most profitable. By targeting core customers, companies are better positioned to create the kind of value that will keep these customers loyal in challenging times. Finally, by reducing costs and enhancing value, synchronization helps protect margins and sets the stage for future growth. While not a silver bullet, end-to-end supply chain synchronization does represent a powerful new strategy for managing risks and deliver value in uncertain times.

About our research

In developing our understanding of end-to-end supply chain synchronization, we conducted in-depth field interviews with 13 benchmark companies. Companies spanned food, equipment, furniture, chemical, packaging, health care, and CPG industries. Most interviews focused on how companies were driving synchronization best practices in North America, but many companies also shared best practices developed from their global operations. Because of the breadth of the topic, the industries sampled, and the different stages of maturity, benchmark company focuses were also broad. Over 100 best practices were discussed. The research team chose the top six best practices to illustrate the synchronization concept. These six best practices were most cited as areas of continued opportunity by many of the benchmark companies. The full GSCI End-to-End Supply Chain Synchronization Strategy white paper can be downloaded at haslam.utk.edu/whitepapers/global-supply-chain-institute/end-end-supply-chain-synchronization.

SC

MR

Sorry, but your login has failed. Please recheck your login information and resubmit. If your subscription has expired, renew here.

November 2020

Supply chains have been in the spotlight like never before over the last eight months. That hasn’t always been a good thing. The perception, reinforced by shortages of products essential to our daily lives, is that… Browse this issue archive. Access your online digital edition. Download a PDF file of the November 2020 issue.To say that these are uncertain times is an understatement. It can be argued that there haven’t been such across the board supply chain disruptions since the end of World War II. For starters, businesses face changes in demand. Unemployment remains elevated while business sentiment on future hires continues to be pessimistic; although recent weeks have seen an abatement in the unemployment rate, future layoffs in industries such as commercial aviation and the oil industry seem inevitable.

These labor market disruptions have taken a significant toll on consumer spending, which declined sharply in the first half of the year and is expected to remain weak for the foreseeable future. Consumers have also changed their spending habits, disrupting traditional revenue streams in a number of industries. And though opportunities exist, many companies aren’t well positioned to take advantage of shifting customer requirements.

Demand disruptions have been exacerbated by supply disruptions. Companies entered 2020 with their supply chains already battered by the ongoing U.S.-China trade war. The pandemic worsened these problems by shutting down key partners, scrambling production and delivery schedules.

Global production, particularly in China, dropped sharply earlier this year and will take time to recover. Meanwhile, distribution networks continue to struggle with shifts in demand, further exposing weaknesses in the supply chain. As companies work to adjust, they are re-learning the lesson that dependable supply chain relationships take time and resources to develop.

Finally, businesses may be facing a slow-burning credit shock. Despite unprecedented moves by the federal reserve, debt laden corporations continue to face pressure. Downgrades of corporate bonds to sub-investment status are on track to reach all-time highs. Moreover, the use of leveraged loans and other practices reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis have reduced transparency and increased the broader economy’s exposure to potentially risky debt. The longer supply and demand problems squeeze profits, the more likely defaults will occur.

And all of these challenges sit on top of a highly charged social and political environment rocked by racial unrest, a resurgence of the COVID-19 virus and an election. It is no wonder that the Atlanta Fed’s Survey of Business Uncertainty has been at historically high levels for most of the year.

The three Ps

Despite headwinds, businesses still expect supply chain managers to find a way through this minefield while continuing to deliver value to customers at a profit. New research by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s Global Supply Chain Institute highlights end-to-end supply chain synchronization as a leading-edge strategy that companies can use to manage shocks, recover stability and set the stage for future gains (See About our research).

Supply chain synchronization focuses on building supply chain capabilities and linking them to a core business driver to create a platform for long-term organizational success. It requires a deep understanding of the core business driver and the creation of a supply chain where physical assets, business processes and people systems (the Three Ps of Supply Chain Synchronization) are intimately linked to its strategic imperatives. Table 1 provides guidance on how companies can manage the Three Ps to develop a synchronized supply chain.

As an example, a global paper manufacturer recently undertook a comprehensive analysis of its manufacturing operations. The analysis revealed that, while some categories rested on operations designed to maximize capacity utilization, other categories rested on operations designed to meet demand at scale. Overall, however, supply chain activities were not clearly or directly tied to meeting specific consumer requirements, which was identified as the company’s core business driver. Through a process of supply chain synchronization, the company was able to realign its supply chain across all categories to drive the business to operate from a more consumer-centric point of view. Flexible equipment, changeover time reduction and agile teams are now the foundation of the company’s operations. These changes have allowed the company to maintain its performance in the current environment.

This type of total supply chain transformation remains rare. Despite improving performance within different areas that comprise the end-to-end supply chain, many supply chain leaders acknowledge that their efforts are often out of sync with the goals and directions of the overall business. In most organizations, strategy discussions usually make only a superficial impact on supply chain operations. Supply chain leaders, to the extent that they are involved in these discussions, are often relegated to supporting roles. And what comes out of strategy discussions often lacks clear guidelines for how the supply chain needs to be managed. As a result, supply chain managers fall back on implementing “popular” supply chain strategies or “optimizing” supply chain processes without understanding the core business driver toward which the supply chain must ultimately be aligned.

As Steve Bowen, CEO of the global supply chain consulting firm Maine Pointe and participant in the research, put it: “The core business driver sets the parameters for business decision-making and has an impact on how resources are allocated throughout the supply chain and operations. Executives and supply chain leaders need to have a clear understanding of the driver and continuously align operations to meet its requirements. Ultimately, they need to build supply chains that deliver total value optimization—support company goals on cost, cash flows and growth.”

Best practices

A handful of leading organizations are working to synchronize supply chain operations with their core business driver in order to unlock the full potential of the supply chain as a source of competitive advantage. In order to better understand what these companies are doing, researchers acting as part of the UT research team conducted in-depth field interviews with 13 benchmark companies spanning food, equipment, furniture, chemical, packaging, health care and CPG industries. The interviews yielded six best practices that companies can follow to more closely synchronize their supply chains.

1. Alignment with the core business driver

Alignment with the core business driver is what makes the synchronization strategy unique. Historically, supply chains have simply tracked continuous improvement on a range of activities without a clear understanding of how (or whether) these activities related to the core business driver. The companies interviewed for this research, by contrast, found that significant waste can accrue when supply chain operations are managed using a narrowly focused “improvement” lens. These companies found that financial metrics were far better at aligning operations to the business driver. They emphasized that all functions needed to actively participate in providing data, experience and knowledge from an end-to-end perspective. Critical areas of understanding that needed to be communicated included a detailed analysis of cost of goods sold (COGS), customer service requirements and areas of waste generation. Finally, while recognizing that a company might operate multiple supply chains and have multiple business drivers, leading companies emphasized the need for every supply chain to focus on a single business driver. If more than one business driver was identified, supply chain leaders placed the most important driver as the centerpiece of their synchronization strategy.

2. Multifunctional leadership

The synchronization best practice mentioned most frequently in interviews was the need for strong multifunctional leadership. This best practice is not unique to synchronization, but is absolutely critical for the success of a synchronization effort. In the face of extraordinary levels of uncertainty, the greatest opportunities for value creation come from managing the seams and intersections of complex value chains. The days of simply running an efficient supply chain are over. Top supply chain executives must have excellent boundary management skills, and the ability to influence both commercial and financial leaders, to succeed in this environment. At the same time, supply chain leaders need to assemble multi-functional teams and task them with identifying initiatives for simplifying and synchronizing workflows across the organization. Teams should include representatives from sales, finance and product research—as well as traditional supply chain functions—and focus on enhancing business processes with an eye toward improving key financial metrics.

3. Value stream mapping

Leading companies emphasized value stream mapping as perhaps the most important tool for executing a synchronization strategy. Three major points in particular were emphasized. First, companies needed to define the value stream broadly. For leading companies, the value stream included everything required for an enterprise to deliver value creation. This included design, source, make, deliver, sell and service. Second, the purpose of the value stream was to deliver the end business objective. Leading companies used the term value stream to focus the organization on the purpose of the system. The goal was to visualize where every part of the supply chain fit into the value stream, so that the entire organization would be fully involved in managing and improving the value stream. Third, value stream mapping was detailed work and the total effort required to map a value stream for a large, global, multi-category business was significant. Teams could lose sight of the objective and get caught up in the grind of mapping the system. Labeling the work as value stream mapping reinforced the critical point that the purpose is to increase total value.

Mapping exercises generate hundreds of questions regarding supply base management, process redundancy and integration, customer fulfillment and more. Building on the value stream map, leading companies first focused on simplifying their supply chains, then standardizing and integrating processes, and only lastly did they move toward implementing a synchronization strategy. In this way, teams were able to achieve tangible, incremental benefits while building the necessary skills and relationships needed to tackle the ambitious end goal of synchronization. Table 2 provides a detailed overview of the process.

4. Dependable supply chain operations

To achieve dependable supply chain operations, leading companies focused on two key aspects. First, they advanced common values across the supply chain. Common values help these companies prevent significant conflicts within and between organizations. They allow management to focus on value creation as opposed to dispute settlement. Common values are especially important in the current environment, where uncertainty can break contracts—and relationships—without collective commitment to value creation goals.

Second, leading companies focused on creating reliable, predictable, zero waste supply chains. A typical supply chain incorporates thousands of activities and transformations. This system is only as reliable and predictable as its weakest link. Importantly, leading companies recognized that a high level of reliability does not guarantee a predictable outcome. For instance, a supply chain with 100 dependent steps, where each step delivered its product on time 98% of the time, would achieve less than 20% on-time delivery of product. Supply chains need to be both reliable and predictable. Reliable and predictable operations enable leadership to work on more strategic capabilities. Conversely, non-reliable or unpredictable supply chains require attention on managing day-to-day issues.

Zero waste directly supports the work of creating a reliable and predictable supply chain. The highest levels of waste are typically observed in areas where people and processes intersect, including product design, integration across units, information exchange and coordination with suppliers and customers. Rooting out waste in these areas produced more effective interactions, leading to better reliability and predictability.

5. End-to-end, digitally enabled visibility

Supply chain visibility played a critical role in synchronization strategies at leading companies. These companies operated on the motto “you can’t fix what you can’t see.” Hence these companies invested significantly in technologies that provided visibility into the end-to-end supply chain. Digitalization of the supply chain has advanced dramatically over the last decade, enabling integrated, platform-based supply chains.

Leading companies have applied these technologies to their synchronization efforts. For instance, companies have used digital technologies to capture massive amounts of data and apply real-time analysis to track traditional variables—such as cost, quality and delivery—as well as agility-based variables—such as time, cash, service and responsiveness. In one example, a heavy equipment manufacturer implemented digital information systems to view its entire global inventory system. Inventory is now visible in manufacturing warehouses, transit, replenishment centers and franchises. This capability has enabled the company to enact inventory sharing processes to increase service while reducing cash outlays.

In addition, leading companies used analytical tools to model the supply chain, simulate solutions and continuously improve systems to deliver optimized total value (service, time, cost, revenue, quality, cash). This capability has become the basis for improved end-to-end planning and replenishment systems using internal and external data to improve how the supply chain is managed.

6. Develop skills and capabilities to execute synchronization

Finally, synchronization requires supply chain personnel to develop new skills and capabilities. Leading companies highlighted some of the most important skills for executing a synchronization strategy. These include the ability to influence others (particularly in areas outside their expertise), multi-functional business process skills and experiences, boundary management, financial literacy, and business analytics and other digital capabilities.

Companies can take numerous approaches to developing the skills and capabilities needed to execute synchronization. One company interviewed by the research team developed a global community of practice (CoP) approach to document and promote key capabilities. Successful work processes were developed, standardized and validated. These processes were then captured by the CoP for training and reapplication. The organization is focused on keeping the CoP alive and current to address the challenges of efficiently managing complex global operations. Other approaches exist as well.

Regardless of the approach, the key takeaway from interviews was the need to shift away from a limited focus on functional skills to a broader focus on talent development. Companies also emphasized the need to find, hire, develop and retain talent as critical to synchronization.

Emerging synchronization strategies

Leading companies are applying these best practices to ensure that all supply chain assets, processes and people are synchronized to the core business driver. An omni-channel retailer, for instance, was struggling before the current crisis to respond to rapidly changing consumer behavior and the threat of disruptive business models. The company first identified internet consumer orders with low average demand and high variation as its core business driver. In order to synchronize its supply chain to these customers, it implemented market leading data analytics that enabled visibility, improved control and optimized inventory levels. The company also streamlined operations to enhance dependability in its end-to-end supply chain. As a result, it was able to decrease working capital by 25%, reduce logistics spend by up to 12% and save tens of millions of dollars in procurement costs.

Not all companies that were interviewed achieved such striking success. Because synchronization is still a very new strategy, many leading companies had yet to achieve full implementation. Other companies were building on partial successes to achieve greater gains. But all of the companies were convinced the synchronization was critical to the long-term growth of their companies.

Most importantly, perhaps, synchronization can help companies weather the challenges and opportunities of economic uncertainty. When shocks occur, end-to-end visibility—coupled with strong relationships—provide a critical foundation for maintaining operations. At the same time, having a clear understanding of the core business driver gives companies critical direction in deciding how best to adjust to new circumstances. In many cases, this means precisely defining the customers or segments whose value requirements best align with the company’s capabilities and are the most profitable. By targeting core customers, companies are better positioned to create the kind of value that will keep these customers loyal in challenging times. Finally, by reducing costs and enhancing value, synchronization helps protect margins and sets the stage for future growth. While not a silver bullet, end-to-end supply chain synchronization does represent a powerful new strategy for managing risks and deliver value in uncertain times.

About our research

In developing our understanding of end-to-end supply chain synchronization, we conducted in-depth field interviews with 13 benchmark companies. Companies spanned food, equipment, furniture, chemical, packaging, health care, and CPG industries. Most interviews focused on how companies were driving synchronization best practices in North America, but many companies also shared best practices developed from their global operations. Because of the breadth of the topic, the industries sampled, and the different stages of maturity, benchmark company focuses were also broad. Over 100 best practices were discussed. The research team chose the top six best practices to illustrate the synchronization concept. These six best practices were most cited as areas of continued opportunity by many of the benchmark companies. The full GSCI End-to-End Supply Chain Synchronization Strategy white paper can be downloaded at haslam.utk.edu/whitepapers/global-supply-chain-institute/end-end-supply-chain-synchronization.

SC

MR

More Risk Management

- Israel, Ukraine aid package to increase pressure on aerospace and defense supply chains

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- More Risk Management

Latest Podcast

Explore

Explore

Topics

Procurement & Sourcing News

- Israel, Ukraine aid package to increase pressure on aerospace and defense supply chains

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- More Procurement & Sourcing

Latest Procurement & Sourcing Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks