Editor’s note: Procurement is changing as a function within the enterprise and as a profession. In this excerpt from Procurement Mojo: Strengthening the Function and Raising it’s Profile, author Sigi Osagie, explains how a focus on business soft skills can improve the effectiveness of procurement within the organization. By clicking on the link, you can read an interview with Osagie.

Effectiveness is not a requirement that is peculiar to Procurement. Rather, it is central to success in any realm of life. My own experiences are adequate evidence for me. I am sure that if many of us examine our personal experiences in successfully achieving things we truly desired in life, we will see clear evidence of the importance of taking the right actions, doing the right things, to get what we want. In some senses, it’s quite a simple notion to grasp: if you want to move forward, you take a step forward; if you want to head off to your right, then you take a step in that direction; if you want a clean car, you wash it yourself or take it to the carwash; if you want some dangerous excitement in your marital life, you get a lover.

I use these simplistic examples because I learnt a long time ago that knowledge doesn’t have to be complex and heavy; keeping things simple always helps my own comprehension and communication with others. In reality, of course, the outcomes we want tend to be far less simplistic than turning left or driving a clean car. Nonetheless, the fundamental concept of doing the right things to achieve the outcomes we want remains the same, even when those outcomes are results as complex as outsourcing a key business process or building a successful Procurement function.

The challenge often comes because we get muddled in our thinking, not helped by the societal or environmental factors that confront us daily, whether in our private lives or in our organisational existence. Economic activity and most organisational endeavours are measured by numbers – gross domestic product (GDP), unemployment, sales revenue, profit margins, ROI, cost savings, and so on. So it is understandable that most of us end up viewing our activities at work and measuring ‘success’ by numbers. Typically, these numbers are direct or indirect measures of efficiency – how much output we achieve for our input efforts.

But efficiency measures never tell us whether the outputs we achieve, or are pursuing, are the right ones. Efficiency just tells us how slick we are at getting the outputs. Effectiveness, on the other hand, forces us to consider what we really want in the first place. Focusing on effectiveness demands that we maintain a strong sense of appropriateness, even in the midst of an efficiency-biased environment. We really have no choice; because, in the long run, whether we are talking about Procurement functions or entire organisations, an entity’s ability to consistently achieve its goals, and, thus, deliver long-term sustainable performance success, depends on the actions it takes. The landscape of corporate history is littered with abundant examples for us to learn from. I was part of some of that history in a small way while at Marconi, as the company fought desperately for survival in the early 2000s.

Hindsight, they say, is a great thing. I can see many things we did greatly in my six years with Marconi. For instance, internal communications to employees during the dark days of negotiating the debt-for-equity swap – the act that saved Marconi for a while – was excellent. We were kept informed of what was being done to salvage the business by regular update briefings, usually via the company’s intranet which employees across the world could access. (The news wasn’t great though; it was like being a passenger on the Titanic after it had struck the iceberg.)

I also recall several strategic moves that, perhaps, we really shouldn’t have made. And you don’t need a PhD in business to work out the first of those: dumping our interests in several other sectors to focus the entire business on telecoms. But let’s not get into the minutiae of that episode; that’s another story, one which has been well covered by the financial press. The bottom line is that we didn’t take the right actions to safeguard the long-term future of the company. This sort of oversight is one that more than a few organisations are guilty of, at enterprise and functional levels.

Procurement and Organisational Success

Many Procurement functions are guilty of such oversight; they fail to take the right actions to strengthen functional capability and raise awareness of Procurement’s aggregate value-add to the enterprise. When we think broadly about the role effective purchasing plays in the success of an organisation, it far exceeds the financial benefits delivered through good spend management. In today’s industrial world, where third-party products and services provision is dominant, the suppliers we bring to the table in procuring goods and services for our organisations are, in effect, extensions of our organisations. If the suppliers are sub-standard, so will our organisation become eventually. If they are stellar performers, we will reap stellar benefits too.

In the same way, when Procurement sources supplies from distant regions, perhaps for cost benefit reasons, we inherently create greater risks in our extended supply chains – risks which inevitably affect the organisational capability of the wider enterprise. We could go on to list several other examples of Procurement’s direct and indirect influence on the capability and success of organisations. How strong these influences are depends on the positioning of the Procurement function. Even if we do choose to focus purely and myopically on the impact of Procurement through spend management, the potential return on investment an organisation gets is obvious. It is a result that directly affects the bottom line, irrespective of the squabbles Procurement often gets into with budget-holders and Finance.

A key challenge for Procurement functions is always balancing the myriad of conventional factors that affect ‘success’ – purchase price, cost savings, non-financial benefits, supply reliability, supply risks and organisational perceptions. But there are other factors to be considered, especially when we talk about long-term sustainable success. Issues like alignment to the corporate agenda, development of human capital and avoiding those internal squabbles, for instance, immediately spring to mind. These are the sorts of issues which impact long-term success but may not always hinder short-term performance results if ignored.

For some Procurement functions success comes in stages. They excel in one or two dimensions initially, then consolidate and expand to tackle other areas, gradually building up the functional capability. We frequently hear of many examples of success, usually in particular aspects of supply management. The nominees and winners of the annual CIPS Supply Management Awards are good examples, as are those nominated across the pond for the Institute of Supply Management’s annual ISM Awards for Excellence in Supply Management. Some are really inspiring chronicles of Procurement people finding their mojo, creating functional organisations that delight their stakeholders while keeping other enterprise benefits flowing. One residential services business successfully revamped its purchasing operations under the leadership of a new Procurement head who was hand-picked for the task. Procurement was transformed into an integrated function with improved focus and people capability, an endeavour that yielded significant financial gains and greater credibility with stakeholders right up to the CEO.

Other success stories exemplify how the pursuit of effectiveness in Procurement can result in game-changer strategies that turn the conventional view of purchasing on its head. There is probably no better public example in corporate history than Gene Richter’s achievements with Procurement at IBM in the 1990s, an effort that contributed in no small way to IBM’s turnaround.

Richter was brought in as Chief Procurement Officer at a time when Big Blue’s standing in supply markets left a lot to be desired. The situation inside the business was not much better, with purchasing activities fragmented across multiple business units. Yet Richter recognised the actions required to deliver the necessary improvements to support the business turnaround. He re-engineered Procurement and instilled an organisational ethos that boosted stakeholder satisfaction ratings by over 100%, while delivering billions of dollars in purchasing spend value improvements. The enhanced purchasing capability helped secure IBM’s position in the marketplace. The company subsequently extended the reach of its Procurement function by providing outsourced purchasing services to external clients. Today IBM is one of the premier global providers in that sector and has frequently been listed in industry rankings of top performers.

Procurement success stories are not limited to developed economies. Even in the developing world, where functional capability tends to be below Western standards, purchasing people in companies like Absa and Sappi have shown how effective approaches to supply management can yield significant benefits to the wider organisation through enhanced supply base alignment. Both companies were winners of the CIPS Pan-African Procurement Awards in 2011 along with several others. It is worth pointing out that in both cases the strategic benefits derived were more important than any related financial gains.

Of course, there are also many Procurement success stories which go unpublicised. In some cases, one- or two-man Procurement functions are delivering real value to their small business employers, making a tangible contribution to organisational success that is easily visible. But all these success stories belie a concrete truth: that most Procurement functions today are still fighting for higher recognition in their organisations, and the capability to showcase the function’s true value-add – they are still searching for their Procurement mojo.

Many widely-available trade publications and surveys provide insights on the perceptions of Procurement among business leaders. One survey reported that almost forty percent of finance directors view Procurement’s influence as detrimental or, at best, neutral. Other reports suggest that people outside the function often feel that dealing with Procurement is exasperating. Such perceptions constitute a damning indictment to us in the purchasing profession.

Things may have changed in the last decade or so, but progress has not been as marked as most of us would like. Still far too few people really understand and appreciate the value of effective purchasing in many organisations. Despite being the function with the most financial impact on enterprise profitability, Procurement is still not perceived as a strategic lever or an enabling function in most organisations. Its reputation is the ball and chain that slows progress. That reputation still centres on a narrow perception of Procurement as a function that exists solely for cost savings, supporting bids, drafting contracts, raising purchase orders, chasing suppliers and general policy enforcement.

We don’t really need others to make assertions for us to learn. We all acquire knowledge in different ways to form our own opinions. Thus, as you read this, think about your own Procurement function and its standing in your organisation. Think too about the Procurement functions in the last two or three organisations you have worked in. And think about insights you have gleaned about other Procurement functions from your professional peers and acquaintances. Is Procurement really as effective as it could and should be in the majority of cases?

Several practitioners and commentators have identified various reasons for the suboptimal perceptions of Procurement that exist in many organisations. The list includes: Procurement functional activities are typically not aligned to business priorities or direction; business leaders do not truly understand the power of effective purchasing in building competitive advantage; business leaders are focused on other organisational priorities; Procurement leaders and practitioners lack the requisite skills, experience and motivation to sell the function’s value proposition; an identity crisis in the broader supply chain management profession blurs functional distinctions and creates misunderstanding for stakeholders; … I am sure we could find one or two other things to add to the list. But before we do, we should hark back to the earlier question about turning up to a gunfight with a knife. The moral of the question – that the onus is always on us to be appropriately prepared – applies perfectly to the predicament many Procurement functions face in their organisations. The onus is on Procurement people to take the actions necessary to get the outcomes they want.

I made an assertion earlier that effectiveness – doing the right things, or taking the right actions, to get one’s desired outcome – is not a requirement which is peculiar to Procurement. In fact, effectiveness is a critical requirement not just for other functions but also the wider enterprise as a whole. In capitalist society, where we mostly worship at the altar of money (whether we like to admit it or not), controlling the flow of funds through an enterprise is important. And, when it comes down to it, only two funds really matter: the money flowing into the enterprise and the money flowing out. For most organisations, the single largest or second largest area of expenditure is third-party spend. As custodians of that spend, Procurement is undoubtedly a critical function, even for non-profit organisations. Thus, the requirement for effectiveness is even more vital for Procurement functions. If third-party spend is not managed effectively to extract optimal value, the long-term impacts on the financial health of the organisation can be dire. This is in addition to the risks posed by a suboptimal supply base that can result from ineffective supply management.

Procurement’s importance to any organisation is profound when properly understood. Many of the companies that have demonstrated long-term success and retained top positions in popular rankings of corporate performance recognise the power of effective purchasing. Harnessing Procurement’s true value proposition is something they have come to master, though the trap of complacency will always be close-by. Companies like Vodafone, Cisco Systems, Coca-Cola Enterprises, Apple, Samsung and several others, many of whom quietly get on with their business and shun the limelight, have reaped the benefits of economies of learning from their repeated efforts to leverage Procurement’s true value-add. Organisations like these appreciate much more the direct impact Procurement has on the bottom line, though such impacts may not always be easily visible or quantifiable in some businesses. Sadly, many organisations – the laggards – do not even display a rudimentary understanding of this impact as yet.

People with enough commercial nous and business experience know that it is far easier to boost a company’s profitability through effective purchasing than it is through sales growth. (Of course, the level of organisational and market maturity are always added factors.) While this is an important element of Procurement’s default contribution, it also constitutes a double-edged sword; hanging the function’s value proposition entirely on its financial impacts risks exacerbating the myopic view of Procurement as a ‘cost savings’ function. We must think beyond the numbers – issues like supply risks, supply base alignment and corporate social responsibility (CSR) can rarely be adequately encapsulated by numbers alone. These are all issues in which Procurement has a lead responsibility.

The Need for “More and Better”

Procurement’s influence on the success of the wider enterprise can not be overemphasised. Many business leaders nod sagely when this issue is discussed. But, judging by the status of Procurement in most organisations, only a minority have grasped the nettle. Yet there appears to be a general acceptance of the notion that organisations should devote effort and resources to securing top-notch purchasing and supply chain management know-how. A number of studies, covering organisations of various sizes in different industry sectors, have explored the fit between Procurement’s role and the strategic development and financial or operating performance of the wider business. The overriding consensus that misalignment between Procurement’s ethos and the enterprise strategic agenda creates economic and non-economic detriment is unsurprising. Those who understand Procurement’s true value-add already know this. But it certainly helps when our instinctive knowledge or professional judgement (or, common sense, as some would view it) is backed up by empirical evidence.

We have ample proof that when purchasing is done effectively it becomes a vital component of sustained competitive advantage. In times gone by it was easy, and appropriate in some situations, to focus organisational and leadership attention on enhancing profitability solely through sales growth. But in today’s world, where the jet engine, the internet and falling telecommunications costs have combined to create a global village, things are radically different. For instance, the continued push for better shareholder returns and higher business efficiencies, combined with competitive pressures arising from a more globalised economy, has created an outsourcing industry that has mushroomed beyond anyone’s imagination. Today the global outsourcing market is estimated to be worth over US$600bn; it has increased a whopping five-fold in a decade, and a significant proportion of that market is offshore outsourcing.

Onshore and offshore outsourcing are great examples of the new world factors organisations of all sorts face today in all three sectors – public, private and charity. We are also confronted by other social, economic and geopolitical factors constantly; such as civil unrest and consequent political instability in the Middle East driving up the price of oil, or natural disasters in far-flung places wreaking havoc on our ability to ship products to customers. For purchasing people, the aggregate impacts of these factors tend to come down to increased complexity, hence risks, in our supply pipelines. The Japanese earthquake of March 2011 is a recent example, one I am sure many buyers of Japanese-supplied stock won’t forget in a hurry. The devastation caused chaos for industrial companies of all sorts, from manufacturers of technology products to car producers. A natural disaster some six thousand miles from its Paris headquarters brought some of PSA Peugeot Citroën’s manufacturing to a stop – talk about global village!

It is not just buyers in PSA Peugeot Citroën that might have suffered a few heart palpitations from supply challenges in recent times. Globalisation and other new world factors have created headaches (and opportunities) for many business leaders. Competitive forces in modern times have certainly made it more difficult to expand profitability simply via the old sales growth route. Consequently, boardroom discussions on enterprise financial performance are increasingly turning to different avenues, not least, better cost control and management of third-party spend. The implications for Procurement are obvious – a growing expectation, though sometimes fuzzy, to make a greater contribution to the financial wellbeing of the wider organisation.

The desire for enhanced Procurement contribution is not restricted to the boardrooms of businesses in the developed world. A growing clamour is also emanating from the developing world where Procurement effectiveness, especially in the public sector, has particular implications for social and economic development. Effective purchasing plays a vital role in socio-economic development; it contributes to trade liberalisation and growth of local enterprise through lower cost of delivering public services. Yet few third-world economies are reaping this benefit in totality.

Of course, third-world countries in Africa, Latin America and elsewhere have very unique problems which are widely publicised. Corruption probably tops the list. A joint OECD-World Bank roundtable in 2003 highlighted an estimated 20% leakage in government budgets in some developing countries due to corruption and fraudulent purchasing practices. In Africa alone, corruption, including fraudulent purchasing, is estimated to cost the continent as much as a quarter of its GDP and artificially raise cost of goods by up to a fifth. And as recently as a couple of years ago, one African finance minister publicly lamented that purchasing activities remained a major source of leakage in national government programmes. But perhaps more poignant for purchasing professionals in the region, he also decried the fact that government structures do not recognise purchasing as a profession, a key failing that needs rectification.

When we amalgamate the varied pixels forming the image portrayed of Procurement from different quarters, the message seems clear: purchasing people must become change agents to champion enhanced Procurement effectiveness. We must strengthen the function; re-define our functional value proposition to illustrate the true benefits we bring to organisations; and we must sell that proposition by delivering relevant results, delighting our stakeholders and building greater organisational awareness – we must find our Procurement mojo.

The recent global recession and the current state of business and national economies offer a great opportunity for Procurement functions to find their mojo. The economic challenges of recent times have galvanised those boardroom discussions, turning mere exchanges into corporate mandates. It is a shame that Procurement still has no de facto seat in the boardroom, enabling more direct influence over those discussions and how the ensuing mandates are executed. In many ways, the absence of a Procurement seat at the top table indicates the stature of the function in most organisations.

Of course, in some organisations with leading purchasing practices the Procurement function already plays a key role in shaping and implementing corporate strategies. Benchmarking surveys and trade publications frequently reveal some organisational traits and approaches adopted by such Procurement pioneers. In particular, many recent studies illustrate how supply management in such organisations has changed, augmenting enterprise strategies to adapt to new world factors. In such businesses Procurement has been elevated up the corporate ranks. Some studies indicate that over fifty percent of Procurement functions in such leading organisations now report to a C-level board executive. The picture is even better in a relatively small proportion of organisations where the most senior Procurement executive sits on the executive board – at the time of writing, Siemens AG and Anheuser-Busch InBev are two examples of this tiny minority.

Undoubtedly, boardroom representation is one of the strongest indicators of any function’s esteem in an organisation. Procurement has come a long way from the days when a move into the department was, in effect, a relegation to the backwoods of organisational existence. But even as recently as the early 1990s, Procurement was still seen as a back-office function immersed in traditional tactical purchasing activities. The more strategic supply management approaches adopted by organisations with leading purchasing practices have helped bolster Procurement’s image and get the function closer to the top table. This is a welcome development, not just for mature purchasing practitioners (especially those who for years have felt like their job is akin to banging their head against a wall 8 hours a day, 5 days a week), but also for the development of the profession as a whole.

Purchasing is not yet widely perceived as a premier league profession; certainly not when compared to, say, marketing, law, investment banking or entrepreneurship. But continued efforts by leading companies to exploit the power of effective purchasing have given Procurement a more important role in the corporate theatre. The recent economic slump has been an added boost as organisations of all sorts have sought to protect profit margins. Suddenly the spotlight is on Procurement and it is shining brightly. Will our performance truly delight the audience?

It won’t be a case of ‘time will tell’. Rather, only those Procurement functions who find their mojo by enhancing effectiveness will indeed delight their stakeholders.

The increased popularity of Procurement in many quarters is a good stimulus to attract new talent and help develop the profession further. They say nothing succeeds like success. The more opportunities the Procurement function has to succeed, and the bigger its successes, the more bright, young talents it will attract. This is an often overlooked fact in the debates on growing Procurement talent. We must remember that in the talent war for new career entrants Procurement is competing with functions like Human Resources (HR), Finance and Marketing. These are functions that are, arguably, significantly more established and more highly regarded in many organisations. Other functional areas that are relatively new to the corporate landscape, such as Corporate Communications, are also competitors in the talent war, especially as they are often perceived to be more ‘sexy’.

Making purchasing an appealing career path is part of enhancing functional effectiveness and sustaining the collective Procurement mojo. No matter how good the bench-strength and competency of your Procurement function is today, it is inevitable that at some point some of your best people will leave. Hence, it is vital to nurture a pipeline of emerging talent, just like many top-flight soccer clubs do through their youth academies. And just as any gifted young soccer player has a choice of youth academies to join, so too does any talented young professional, undergraduate or school-leaver have a choice of professional paths to embark on.

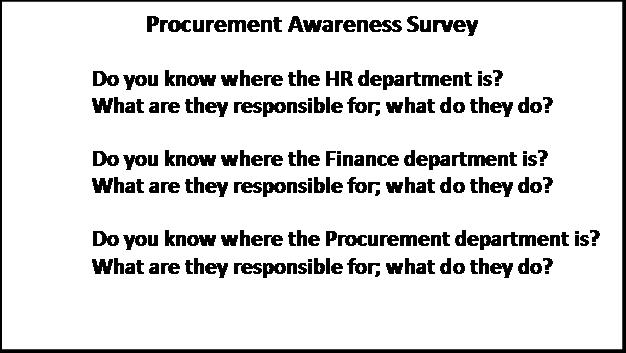

Some purchasing people might disagree with my assessment of the function’s standing in most organisations today. My own Procurement team at one erstwhile employer didn’t quite get my drift initially. So I encouraged them to do a simple test: to stand at our Reception or one of the elevators with a clipboard and carry out a random survey of at least twenty-five passersby, at any time on any day of the week, asking each person the following questions:

1. Do you know where the HR department is at this company? What do they do there; what are they responsible for?

2. Ask the same questions, but for Finance

3. And for Marketing

4. Then, ask the same questions for Procurement.

Rightly or wrongly, perception can sometimes be more important than reality, especially in large organisations. Trying to argue Procurement’s case in a mire of organisational misconceptions is like complaining about your opponent who turned up to the gunfight with his pistol while you turned up with that knife. Raising the profile of our newly-created Procurement function at that former employer was one of our key priorities. We never did do the survey – we didn’t need to; I was eventually able to get the team to understand the importance of our profile, and they ‘got it’. But perhaps a similar benchmark survey, as illustrated in figure 1.1, might be an interesting experiment in your own organisation.

Figure 1.1 – Sample Procurement Awareness Benchmark Survey

What do you think the results would be? Will people know as much about Procurement as they should, considering its importance? Will they know as much about Procurement as they do about the other functions? And will they have a robust awareness of what purchasing is really about?

If you are really interested in enhancing your Procurement effectiveness, I would suggest sitting down with a pen and paper and noting down your opinions on the likely answers to these questions. What do your own opinions reveal about the effectiveness of your Procurement function?

It could be even more interesting to have a few detailed discussions with your most important consumers or internal customers – the budget-holders, whose third-party spend Procurement is accountable for managing for value. What do they really perceive Procurement’s role to be? What benefits, or value-add, do they feel they get from Procurement? Do they feel their needs are well met? Do they feel they have a functional ‘business partner’ who adds something valuable to their attainment of their own business objectives? How do they feel overall about Procurement’s service to them – disappointed, indifferent, satisfied or delighted?

Irrespective of what you or your Procurement team members think, it may be instructive to carry out this survey anyway. It could prove to be a conduit to critical insights on finding and boosting your Procurement mojo.

Countering suboptimal perceptions of Procurement is integral to enhancing the effectiveness of the function. It is a vital element of how we find the Procurement mojo, through raising awareness of the function’s true value proposition. This may be less of a requirement for organisations with high calibre Procurement functions, where the value of effective supply management is fully appreciated. But such organisations are the minority. And, typically, they tend to be large multinational corporations. Yet most of us work in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Even with the added significance Procurement has garnered due to the global recession, in majority of organisations the search for the Procurement mojo remains unfulfilled.

Procurement Effectiveness is Foundational to Sustainable Success.

When we start focusing on Procurement effectiveness things start to fall into place. I mentioned earlier that too many Procurement functions give overriding focus to the numbers, an understandable trait given that we operate in a numbers-driven commercial world. Even in organisations with leading purchasing practices, Procurement success still typically imbibes the amount of savings delivered. When we focus too much on the numbers we fail to leverage the power of our collective imagination and converged effort when channelled towards building sustainable capability. Think about the power of Bill Gates’s vision of a PC on every desk way back in the early 1980s, and how that vision (not merely the projected sales revenue!) propelled Microsoft to a position of dominance and long-term success in its sector. Or think about the Apple team that developed the iPhone and brought it to market, a product that revolutionised the mobile phone industry; do you think they were inspired by the number of handset sales predicted or the vision of their game-changer product?

Some Procurement functions get hung up on other things – processes; tools; contracts; strategy; how much spend they have under control; the department’s name; and so on. The name of the profession or the department, the functional strategy, the organisational structure, the enablers (processes, systems and tools), the cost savings we deliver… are all important to varying extents. And they require corresponding levels of our attention, along with other aspects of ‘the purchasing job’. Most of these issues come with the territory, so to speak. But we must recognise that they are all subsets of the Procurement mojo – that special spark, an amalgamation of these and other subsets that creates long-term sustainable success when pursued coherently.

All told, recent evidence does indicate that more and more organisations are starting to recognise the importance of effective purchasing and its potential strategic value. But only a small proportion is able to leverage that value. No doubt, the global recession forced many organisations to accelerate the pace at which they build a comprehensive understanding of how they can gain that leverage. It is a fantastic opportunity for Procurement – Procurement functions can find their mojo at the very time others want us to; we can exploit the focus Procurement is getting under the spotlight in these times. But to do that Procurement people must imbibe a different ethos to our own perspectives on our functional role and how we go about gaining success in that role.

For starters, we must put aside our conventional beliefs of what is important in the purchasing job. We can begin by learning from our own organisational existence as a function. The issues that prevent most Procurement functions from achieving long-term sustainable success are not the technical issues we traditionally focus on. Rather, they tend to be the ‘soft’ issues, the very issues most of us give inadequate time and attention to. For instance, the critical challenges I mentioned earlier – functional leadership skills, staff competency and stakeholder relationships – are significantly more vital to success than factors like sourcing strategies, purchase-to-pay (P2P) processes or e-auction platforms. The overriding consensus from relevant studies demonstrates that Procurement capability and success relates directly to the calibre of leadership and people capability in the function. My experience with various organisations and discussions with peers support this. These ‘human factors’, more than anything else, are the underlying attributes that drive performance.

Of course, ‘performance’ is multi-faceted. So delivering sustainable performance success requires a holistic approach, one that imbibes these critical human factors or soft issues as well as other more technical aspects like Procurement systems and tools. The key to this holistic approach is the overarching goal of enhancing Procurement effectiveness – giving prime focus to doing the right things to achieve the performance success we want. The conventional efficiency measures we focus on as indicators of performance are always reflections of the past; we have already made the input effort and witnessed the output.

Focusing on effectiveness, instead, forces us to question the actions we are taking in the present, today, and how they relate to the end-goals we are pursuing.

Efficiency is the well oiled machine that enables us to achieve more output with less input, the slickness that gives us a bigger bang for our buck. Being efficient is important for success. But it is only half the story; the second half at that. The first half, the more important bit, is to be effective.

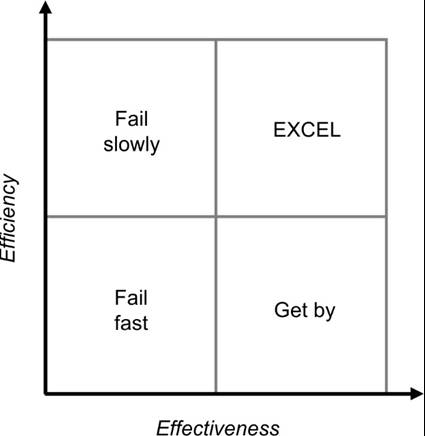

As indicated in figure 1.2, efficiency without effectiveness leads to failure, it’s just a question of how fast or slowly failure comes.

Figure 1.2 – Effectiveness and Efficiency

One of the biggest challenges we sometimes face is that effectiveness is often difficult to measure. Here again, I find the approach of simplicity invaluable. To assess Procurement effectiveness you can simply question if what your Procurement function is focusing on – the key actions and initiatives you are expending effort and investment on – will deliver the outcomes you want. If developing sexy sourcing strategies, implementing a best-practice P2P process or delivering bucket-loads of savings do not yield improved functional capability or heightened recognition of Procurement’s value-add in the enterprise, then you must go back to the drawing board.

Countless research studies and industry surveys have been carried out which illustrate the vital link between effectiveness and achieving performance results consistently. Time and time again we hear many eminent people and prominent business leaders concur on this. As Abraham Lincoln is said to have put it, “Things may come to those who wait, but only the things left by those who hustle.” Waiting for your Procurement mojo to materialise without doing the right things to manifest it is like waiting for a ship at the airport. Success in personal and organisational life is always preceded by the hustle for that success. My own research on management effectiveness and organisational performance, coupled with my career experiences, were enough to turn me into a convert; perhaps, because I, myself, had suffered the consequences of demotivation and failure to achieve my objectives due to my ineffectiveness early in my career.

Years later, when I started coaching and mentoring supply management teams to boost functional effectiveness at various organisations, it wasn’t just to achieve the tangible goals I had been tasked with. It was also to grow the individuals. When we focus on Procurement effectiveness, and, thereby, recognise the critical importance of those soft issues like people capability, it brings clarity to the connection between fulfilling organisational goals and the growth and aspirations of the individuals in the organisation. Procurement effectiveness allows us to fulfil the hungry spirit we all have, the innate desire to be part of something worthwhile, to gain more from our work than the salary we are paid each month. It draws our attention to the added benefits to individuals in the Procurement function, the people who actually do the purchasing work.

You reading this now may be one of those individuals. Finding your Procurement mojo in the work you do is an element of sustaining the effectiveness of your Procurement function. At an individual level, remember that your Procurement mojo won’t come looking for you unless you go looking for it. So think about your own effectiveness in carrying out the responsibilities of your role, and how that augments the effectiveness of your team, or not. You might need to alter your personal perspectives, thinking patterns and behavioural attitudes in several areas. You might, for instance, need to enhance your insights on and appreciation of ‘stakeholders’, starting to view them instead as ‘customers’, ‘consumers’ or ‘investors’. Such attitudinal changes help enhance effectiveness at a personal level, which feeds functional effectiveness.

The pursuit of Procurement effectiveness forces and enables us to create a functional context in which people can flourish and grow, providing benefits that far exceed the obvious and direct financial returns to the wider enterprise. Achieving those benefits is never a done deal though. The changing nature of business and the societies we live in today means that Procurement functions can never become effective and then rest on their laurels. Organisations restructure, recessions come and go, new political and societal issues arise constantly – it is the nature of our existence today. Few businesses worried about corporate social responsibility twenty years ago, yet it is a key topic in many company annual reports today. Few Procurement functions worried about child labour or slave wages in their extended supply pipelines in times gone-by, yet these are now important issues for many of us due to the impact on corporate image, aside from our personal ethics. One of the organisations I mentioned earlier as a Procurement success story broke up its centralised purchasing some years later, negating some of the long-term benefits of the prior Procurement transformation. These are all examples of the dynamic nature of our new world, a dynamism we must contend with continually. Keeping our focus on Procurement effectiveness enables us to do this.

In some of my talks on supply management, leadership or organisations, I often share the tale of Vincent to simplify the meaning of effectiveness. In the days soon after the national lottery was first launched in the UK, Vincent had gone through a life-planning exercise in which he decided that what he wanted in life was to enjoy a millionaire lifestyle, with all the trappings that would bring. Having clarified his life goal, he decided that his route-path to achieve it would be to win the lottery. So, come Saturday evening, shortly before the lottery draw programme aired on TV, Vincent was up in his bedroom, on his knees, saying a prayer, “Please God, please God, let me win the lottery.” The lottery draw TV programme came on, the presenters read out the winning lottery numbers and Vincent didn’t win. The following Saturday he was up in his bedroom again, on his knees repeating his prayer, “Please God, please God, let me win the lottery. I promise to take my wife shopping, to be nicer to my kids, to give some of the money to charity…”

The lottery draw programme came on TV shortly after, the winning numbers were read out, and, yet again, Vincent didn’t win the lottery. But Vincent had one of the important traits we all need for success – persistence. So come the next Saturday, there he was again on his knees in his bedroom, “Please God, please God, let me…” Before he got any further in his prayer he suddenly heard a great, booming voice coming from nowhere and everywhere, “Come on man, will you stop hassling me; at least meet me halfway and buy a ticket!”

Just as you can’t win the lottery without buying a ticket, so too can you not achieve sustainable success without doing the right things to bring about that success.

Procurement functions that are serious about ‘winning their lottery’, achieving the functional outcomes they thirst for – where the function is strengthened and has high regard in the wider organisation – must take the right actions to bring about those outcomes; they must find their Procurement mojo.

Enhancing Procurement Effectiveness.

The search for the Procurement mojo, how we enhance Procurement effectiveness, forces us to think critically about those aforementioned outcomes. You must start by recalibrating your deeply held conventional beliefs of what performance success means to Procurement. The ‘key performance indicators’ (KPIs) we commonly adopt are exactly what the phrase infers: they reflect what we view as the key dimensions of Procurement performance and the measures we use to establish how well we are doing. As shocking as it sounds, some Procurement functions do not even measure their performance. And for those that do, the principal KPIs typically concern financial benefits and regulation or governance. The most common examples include cost savings or purchase price variance; Procurement ROI; spend under management; and supplier performance. But where are the measures that indicate how well we are doing with building the skills and competency of our people, the same people who do the work? What about the measures that tell us whether or not we are succeeding in serving our internal customers robustly, delighting them in a way that feeds a positive perception of Procurement and its value-add? And which measures tell us whether or not Procurement is appropriately aligned to the corporate strategic agenda?

Many years ago I was appointed to lead a regional Procurement function at a global FTSE 250 business. The instruction from my boss, the regional Procurement VP, was to “…sort the place out.” I went in and found a department suffering a complex malady of everything that could be wrong with any organisational unit – inconsistent job titles; an acute lack of focus and direction; poorly defined responsibilities; broken processes; poor team spirit; everyone running around like the proverbial headless chickens, yet operational performance was significantly below par… It was as dysfunctional as it could get, and it was clear to me that the department needed a complete turnaround. In defining some clear goals and related KPIs for the group, I found myself in a debate with my VP on the importance of measuring ‘Organisational Health’, using ‘Staff Attrition’ and ‘Sickness Absence’ as appropriate KPIs. He eventually agreed with me.

If you are going to revamp the culture and entrenched ways of working in a team of almost fifteen mature professionals, it goes without saying that the personnel will have to cope with a significant amount of unsettling change. Some may struggle to cope; and it may be more effective to encourage others to seek their destinies elsewhere. Whatever the case, the stress of the change will impact the health of the organisation, hence its capability and performance, just as stress impacts us as individuals and, thus, our work performance.

Recognising the vital importance of the human capital element of Procurement capability, and imbibing that recognition to our definition of performance success, is not just critical for Procurement functions going through change; it is a prerequisite for all Procurement functions. It is part of the recalibration we must go through as we search for our mojo to enhance Procurement effectiveness.

We must redefine Procurement’s value proposition, starting by extending beyond cost savings and other traditional notions. If we examine Procurement functions that are effective and continue to achieve long-term success, we can amass a different set of pixels which give a more progressive picture of Procurement’s true role in organisations today: to harness the power of supply markets for enterprise success and competitive advantage, in a safe, ethical and cost-efficient manner.

Enhancing Procurement effectiveness affords all Procurement functions a roadmap for achieving our true functional obligations. It enables Procurement to go about selling and delivering the value it brings to the wider enterprise with greater success. As the model in figure 1.3 illustrates, enhancing Procurement effectiveness requires focused actions in 5 key areas:

1. Building an effective Procurement organisation

2. Deploying enablers – processes, systems and tools – that are fit for purpose

3. Managing the supply base robustly

4. Applying an appropriate framework for managing performance

5. Building the Procurement brand through positioning, stakeholder management and effective public relations (PR).

These are the five critical steps Procurement functions must take to find their mojo, building effectiveness through strengthening the function and raising awareness of its value proposition in the wider organisation.

Each of these actions entails varied challenges for different Procurement functions, depending on the current state of functional effectiveness and maturity, and the prevailing perceptions of Procurement in the wider enterprise. Some of these actions require new ways of thinking and executing for most Procurement functions. In the next few chapters we examine what each of these actions means – how each aspect fits into a coherent, holistic approach to enhancing and sustaining Procurement effectiveness, and what Procurement functions have to do in executing these actions.

Some areas require more detailed exploration as they are elements of Procurement effectiveness we traditionally give less attention than we should. Others may be easier to grasp for many purchasing people; so, as much as possible, I will avoid trying to ‘teach granny to suck eggs’ in those areas.

Whatever the case, having explored each of these five steps in detail, you will end with a robust insight to the Procurement mojo and how to enhance Procurement effectiveness to enable long-term sustainable success.

Reprinted by permission of Management Books 2000 Ltd. Adapted from Procurement Mojo: Strengthening the Function and Raising it’s Profile. Copyright 2014 Sigi Osagie. All rights reserved.

SC

MR

Latest Supply Chain News

- Tech investments bring revenue increases, survey finds

- Survey reveals strategies for addressing supply chain, logistics labor shortages

- Israel, Ukraine aid package to increase pressure on aerospace and defense supply chains

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- More News

Latest Resources

Explore

Explore

Topics

Procurement & Sourcing News

- Israel, Ukraine aid package to increase pressure on aerospace and defense supply chains

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- Blooming success: The vital role of S&OE in nurturing global supply chains

- How one small part held up shipments of thousands of autos

- More Procurement & Sourcing

Latest Procurement & Sourcing Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks