Earlier in this book, we looked at the origins of procurement, along with some of the early approaches to spend analysis and the development of appropriate categories as a basis for strategic sourcing. These approaches provide some guidelines into the roots of the current radical shift under way in procurement, as well as some of the pioneering efforts to build strategic capability.

This chapter is designed to offer some insights into how procurement has evolved. We introduce a maturity model to help the reader understand the levels at which different procurement functions are capable of operating at, and the journey of change that organizations move through as they improve. This relates back to our idea of change as a core necessity for success. Procurement needs to change, and a refusal to do so will most surely result in its demise.

Here we look at the value of procurement to the enterprise; how this value is delivered into the business in terms of the service mix – that is, how procurement performs, its level of capability; what level of capability we have today, or need to change; and how efficient and effective procurement is in the execution of its role.

Today’s global marketplace is perhaps best described as unpredictable: increased exposure to shocks and disruption risk pervades economies, financial markets and supply chains like never before. Complexity exacerbates the problem; even minor mishaps and miscalculations can have major consequences as their impacts have almost immediate effect. Some of the biggest changes occurring in today’s global environment were enumerated by Handfield et al in a study of global supply chain executives in Europe, North America, Brazil, India, China, and Russia.

Organizations continue to grow their supply chain global footprint

Organizations in multiple sectors are continuing to pursue global growth strategies that focus on expansion into new regions. In particular, the focal BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) represent major targets for expansion, but with them come a host of new problems that enterprises have little to no experience in dealing with in terms of logistics capabilities. Major growth strategies are driven by economic realities, currency movements, government regulations, or access to existing logistics networks. With globalization, the need to partner with local logistics service providers becomes an imperative. Such providers understand domestic transportation issues, and can plan to develop long-term solutions to complex local distribution challenges.

As companies expand globally, so does supply chain complexity

Globalization of organizational supply chains is continuing to expand as organizations seek growth markets in the BRIC countries, which has proven to be a lucrative target but has also changed direction. Globalization is now increasingly linked to labour costs in countries such as China, as well as fuel costs and regulatory shifts, which are in turn driving a dramatic impact on where companies source, where they produce, and the complexity of processes required to sell to the customer.

This complexity is occurring in many forms. First, products are becoming more complex, as organizations need to create more diverse sets of options, packaging designs and logistics arrangements. Customers increasingly want customized solutions, and require specific logistics delivery requirements. This means that companies need to have more facilities in more countries, with more suppliers, greater diversity in product and packaging needs, more e-commerce and other market channels, and more part numbers. Complexity is also occurring due to increases in local delivery requirements. In many emerging countries, there is a massive expansion in small neighbourhood stores, which brings a strong challenge to distribution networks. Small stores translate into an increase in deliveries and a decrease in size of truckloads. Layer on top of that the spread of urbanization, the economic uncertainty, military conflicts and political volatility, and you have a powerful set of possible complicated interactions to contend with.

Increased globalization brings increased risk of supply disruption

The rise of global markets and the decline in ‘cheap’ labour costs are profoundly influencing where companies source, produce, and the complexity of their processes and operations. Risk is accelerating, and every two weeks companies encounter some sort of logistics problem as a result of volcanoes, wars, tsunamis or other complications. Another major source of risk is the unreliability of global logistics channels, especially the challenges associated with ocean freight lines, which are becoming increasingly unreliable. Labour issues at ports, ships with greater capacity, port capacity and multiple other issues are driving executives to worry about the status of their shipments and whether they will reach their destinations in time to meet customer requirements.

Regulatory requirements are a big part of complexity

As the global footprint of organizations worldwide expands, by far the biggest trend that emerged in all of the interviews (undertaken by Handfield et al) was:

• the increasing complexity of logistics and supply chain regulations;

• protectionist policies;

• product regulations;

• compliance to customs;

• trade;

• local content issues;

• security requirements.

As the private sector seeks to expand its growth in emerging countries, there is increasing pressure economically in these countries to levy import codes and product restrictions to drive revenue and protect local industries. The barrier of regulatory issues is a shifting target that is continually changing, yet the fines and penalties for non-compliance are on the rise. These regulations render it more difficult to meet increasing customer requirements for reliable product delivery, and make it challenging to be able to plan using normal lead times, inventory requirements and scheduling. Multiple interviews by Handfield et al reveal the complex and shifting nature of government regulations, making it more evident than ever that ‘the government is part of every supply chain!’

Logistics network redesign and customization

Many of the companies interviewed in the study noted that outsourcing is on the rise and, as this occurs, increased customization of delivery service and logistics service requirements are on the rise. Customers are relying more on third parties not just to deliver products, but also for increasingly value-added activities. Similarly, manufacturers are being asked to develop customer-specific logistics solutions, and must be able to develop elaborate systems to deal with different customer requirements globally.

Challenges in supply chain and logistics infrastructure

An increasing number of companies note that logistics infrastructures have not been upgraded in many years, and are beginning to show signs of wear. Similarly, the growth and migration of individuals to major urban areas is straining infrastructure, and as companies grow their footprint in emerging countries they are finding that the infrastructure was never there to begin with. A movement of shops from rural areas to the suburbs and urban centres is under way in many cities, yet the numbers of bridges and roads into the city is fixed. In countries such as India, for example, there simply is no logistics network available – just a series of cities separated by small roads and a small railway.

Increasing sustainability pressure

As the global footprint of organizations worldwide expands, by far the biggest trend that emerged in all of the interviews was the increasing pressure to drive sustainable logistics solutions, reduce carbon footprints and other pressures. Proactive companies are looking to sustainability as a source to exploit competitive advantage not just for their brand, but for operational improvements and inefficiencies in the supply chain. One example is that operators of the largest truck fleets in the United States are in the process of converting their fleets to natural-gas-powered trucks. Experts predict that the total fleet of trucks could increase by 30 per cent or more in five years, as the cost of these trucks comes down by 10–20 per cent.

What does this mean?

The importance of these trends leads to the conclusion that understanding and mapping out your supply chain will be more important than ever. You will need to know who is in your supply chain. Who are your supplier’s suppliers, and who is distributing your product, particularly in emerging countries? This is often difficult to grasp, and requires a systematic analysis of who the players are in your network, their relationship to one another, and competing interests that may not always be aligned with those of your sustainability initiatives.

You will need data systems to collect and consolidate technical information on your suppliers and their process inputs and outputs in the supply chain, to be able to construct value stream maps, life cycle analysis, carbon footprints and other required documents. Current systems are often unable to do so. Organizations are beginning to exploit new mobile technologies and social media to compensate for the inability of current enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems to capture what is happening in your supply chain.

You will need both internal parties and external parties (customers) to value the transparency and efficiencies that are gained, and be able to place a return on investment (ROI) on the benefit of complying with sustainable requirements. In the case of some areas, such as labour and human rights violations, this is increasingly tricky to do.

Can procurement embrace complexity?

To some extent, contemporary procurement practice (as described in Chapter 1) is faced with more challenges than ever before. Not only must executives drive a relentless pursuit of innovation and operational excellence, but they must also do so in the face of risk, volatility and massive global complexity in the supply chain. Ironically these increased levels of complexity in modern business have presented an unheralded opportunity for procurement to evolve its value proposition to the business; shrewd procurement leaders have used the prevailing conditions to drive change within procurement and across the enterprise.

That said, this is something of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, global supply markets have never offered so many innovations to those willing to embrace them. On the other, there is only so much that procurement can do with limited time and decreasing budgets, which makes achieving the demands for year-on-year cost savings increasingly difficult. Of course, there have been many organizations that have not been sitting idle. These organizations have reinvested any or all of their hard-won efficiency gains into capabilities that are focused on delivering procurement effectiveness. One of the key capabilities that emerges in the face of this complexity is the value of building a ‘networked economy’. This refers to the ability to effectively create the right set of partners in the network, and together to create a seamless and integrated channel for the free flow of information, products and services. In the modern ecosystem, it is the ‘best supply chains’ that win, not the individual organization. And this is where procurement has the ability, like never before, to lead the charge and herald early success in this new era.

Defining procurement performance and procurement value

Efficiency and effectiveness are the two dimensions of procurement performance. Against these dimensions one can understand what makes a procurement organization a leader in the field or, conversely, a laggard. One can also apply a similar notion to define procurement value. For top-performing procurement organizations, the attainment of this leading practice is not in any way temporary. Rather it is a continuous journey, as the bar keeps getting raised on existing performance in a desire to maintain competitive advantage. There is always something new, a challenge, which requires procurement practitioners to develop newer and more strategic sources of value that procurement (and the supply markets) can deliver. Increasing value is very different than simply setting new targets on the same old measures – and this is a very important factor.

Value – the holy grail for procurement

Value is arguably the most overused term in business today. It is therefore important to clarify its definition and its relevance to both procurement and the enterprise. In Peter Drucker’s celebrated book Management: Tasks, responsibilities, practices (1974), he says: ‘The final question needed in order to come to grips with business purpose and business mission is: ‘What is value to the customer?’’

This in itself is possibly the most important question business leaders can ask themselves, and yet it is the one that is asked least often. A possible reason for this is that business leaders usually think that they know the answer. In their rather narrow view, value is frequently what they define as quality. This definition is incorrect and Drucker goes on to say: ‘The customer never buys a product. By definition the customer buys the satisfaction of a want. He buys value.’

So value is, in essence, utility – that is, the total satisfaction derived from a good or service. Whilst the utility a customer derives from a good or service is difficult to measure, we can assume that consumers will strive to maximize their utility. The term value has to some extent been diluted as it is frequently used loosely and in a number of contexts; but there are a few things we can be certain about – value is relative to an alternative, ie value cannot be judged in isolation. Value is composite and decomposable; value can be analysed into a set of value drivers.

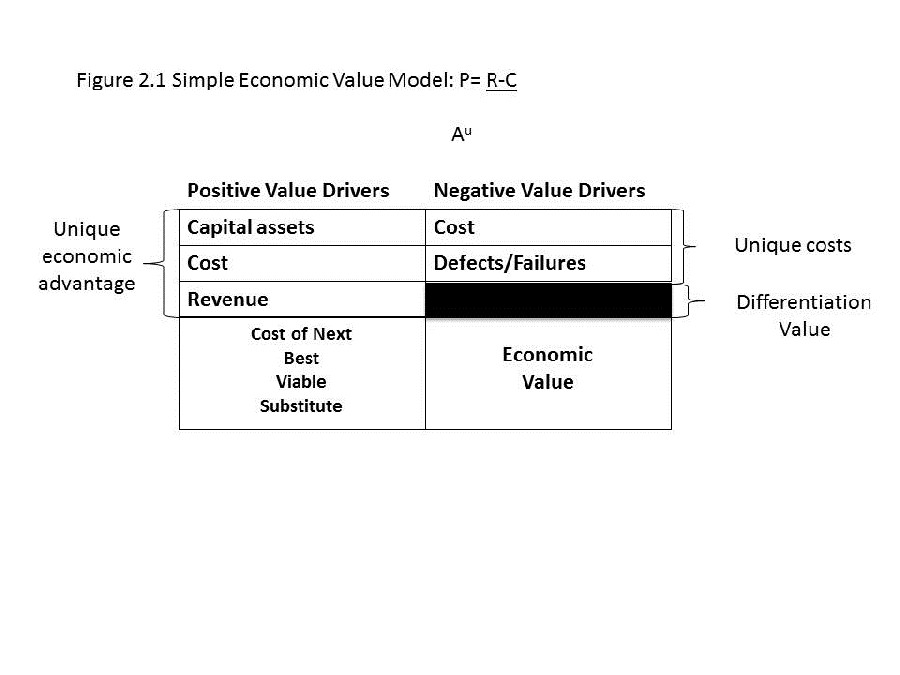

If we look at value in business-to-business relationships it tends to be economic in nature. If we look at this economic value aspect, we can ascertain that value is the measureable and quantifiable. For example, economic value can be seen as cost or revenue. A useful way to quantify economic value is shown in Figure 2.1 in a simple economic value model.

There should also be a mapping from the value metric (the way in which the customer gets value) to the pricing metric (the way in which the seller charges for value). For example, the value of a can of paint may derive from the area covered, while the price is far more likely to be quoted in volume.

Value management has become a hot topic in the business world. Advocates proclaim that value creation and capture is the holy grail – its goal to ensure sustainable and profitable revenue growth for the organization. Value management relies on multiple streams of information from inside and outside the organization. Both internal and external perspectives are necessary. Information about customers, competitors, demand, offers, costs and production constraints are all used in value management, and procurement is well placed to make this part of its contribution to the success of the organization. Put simply, value management delivers profitable growth and it does so because innovation is focused on products and services that provide value to the customer.

Executives recognize that supply management must adopt a more strategic approach that targets performance beyond simple cost savings. To some extent, the field of supply management has become more enamoured with strategic sourcing, to the exclusion of the most important party in the supply chain: the internal customer. As one CPO we interviewed at a major oil and gas company emphasized:

Procurement has got too hung up on being ‘world class.’ Procurement is simply a set of tools on a tool belt, but the real wave of change involves understanding the business well enough to apply the tools that will drive the most effective model for each of the operating groups and geographies we are in. We have a strategy that is focused on ticking the boxes around applying the tools. But we are too focused on getting an answer, rather than an outcome that matters to our stakeholders. We want to create nice 2 x 2s to label our suppliers, rather than generating and delivering a coherent strategy that defines how we work with them to meet our business needs.

This characterization of procurement recognizes a new set of value drivers that go beyond cost savings: understanding internal customer requirements, and codifying these requirements into a coherent statement of need that can be understood by the external supply market. In a sense, this is a type of ‘congruent capability’ in that it enables procurement to link internal and external parties that are mutually dependent on one another. Congruent capability is what an executive we interviewed was referring to when he identified the ideal of creating a ‘virtual integrated company’ where ‘the existence of suppliers is an explicit outcome of a strategic decision to buy versus make. Implicit in this decision is the question of whether an organization is willing to manage the standards, discipline, execution, fixed capital investments, etc of the ‘make’ decision, versus the sourcing, negotiation, contracting and supplier signals associated with the ‘buy’ decision.’ As the primary boundary-spanning interface between the internal and external domains of the enterprise, purchasing has an exclusive mandate to ensure congruency in performance outcomes between the stakeholder’s expectations and the supplier’s resulting performance.

The types of congruent contributions that procurement is capable of providing include:

• product innovation and technology development;

• knowledge sharing and new process capability development;

• multi-tier supplier integration;

• mitigation of supplier risk;

• supplier performance improvement and capability augmentation;

• supplier financial disruption avoidance;

• sustainable supply chain improvements.

Supply management leaders are unanimous in their call for an evolutionary approach to procurement transformation, through the improved alignment of internal stakeholder requirements with an emerging and growing global supply base. Procurement is expected to deliver innovation often from the supply base and this is reflected in the end product or service. Any innovation that does not provide additional value relative to the best alternatives is in essence money wasted. But there remains the perennial debate regarding how procurement tangibly benefits the business.

Many people in supply management and for that matter in the wider business community still lump value and performance together, but they are very different things indeed. Procurement can perform extremely well on a very narrow value proposition. As we know only too well in many organizations, procurement is only measured on purchase order processing and tactical negotiations, which is seen as decidedly average across a spectrum of high-impact procurement processes. So which is better?

To get better value, do you need to spend less or perhaps ensure that more of your expenditure is conducted wisely and brings with it the value that then creates competitive advantage? Procurement value is therefore defined by procurement-led improvements that safely tap supply market power to increase spend value, which is about getting more out of the expenditures you make with your supply base.

Businesses and their CPOs have two choices they can make to maximize their expenditure value through their supplier expenditures. First, they can simply decrease spend magnitude by reducing consumption as well as total cost of ownership (TCO). TCO includes prices, other landed costs, capital costs and the cost of procurement. Second, CPOs can increase the utility they and the business derives from spend to better support stakeholder objectives.

Utility (and thus value) are defined then in the eyes of the customer. These customers include budget holders, requisitioners, shareholders, regulators, suppliers and procurement staff. For procurement to improve spend value, it must improve the value of the services it delivers to the enterprise in order to help it safely tap supply market power to support its mission and create strategic advantage.

Procurement value is simply about offering and executing high-impact procurement services that tangibly and, probably more importantly, visibly increase the value of the procurement team’s spending. So, for procurement, efficiency and effectiveness is paramount in defining its performance. And of course it is on this that expectations are built.

If the CEO was to ask you ‘how much might that price cost the business’ could you answer?

Procurement has for some time been very conservative within the ‘business’. Its practitioners in the main tend to be reactive in mindset and need to move into a more forward-looking posture. They must develop their commercial skills and better manage working capital, enterprise process sourcing (how capability should be delivered, ie make versus buy) and tapping supply markets for innovation. Supply assurance and purchase cost reduction are where many practitioners operate and are the foundations for value management, but procurement practitioners need to evolve to produce greater value by getting more involved in stakeholder processes earlier. They must also become tech savvy too. The best procurement people will have well-developed skill sets in process capabilities supported by technology. The use of analytics will move procurement beyond the ‘commoditized’ technology offerings they utilized traditionally. These bimodal procurement professionals will move the function beyond supply-sided strategic sourcing to earlier and deeper involvement in stakeholder processes.

Contemporary businesses are receptive to procurement taking on more challenging categories of expenditure and responsibilities that give a step change in performance. However, procurement needs to earn the right to move into these categories and this comes from building reputation and developing sustainable improvements. Procurement practitioners need to sell the procurement value proposition, develop capability and execute to improve performance as procurement value proposition relates to the alignment of capability and performance.

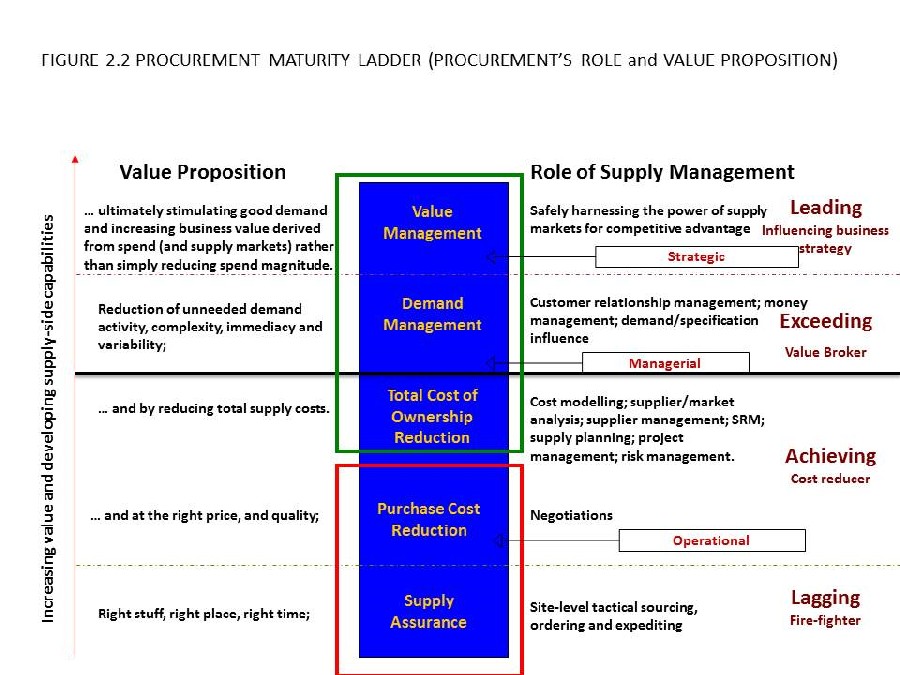

Figure 2.2 sets out a maturity model for procurement and supply management. As the capability of the procurement organization moves up the ladder, so its role and value proposition increases accordingly – moving from ‘laggard’ at the very bottom of the ladder where the function is focused on low-level tactical activity to a ‘leader’ role where the procurement organization directly influences corporate strategy.

The right stuff

The procurement maturity ladder categorizes the role of supply management at four different levels of performance. It equates each level of performance to certain attributes and articulates the value proposition of procurement to the business at each performance level. This is set against value proposition on the left-hand side, and role (performance and capability) on the right-hand side: we can evaluate and identify the increasing performance levels of procurement and its value to the business as it climbs the ladder.

The levels of performance and capability accumulate as the procurement organization evolves from the lowest level of the clerical role, engaged in sourcing, ordering and expediting, where the primary role of procurement is supply assurance through to value management role where procurement is directly influencing the business strategy and is harnessing the power of the supply markets for competitive advantage. As procurement moves from one classification to the next, it takes the attributes of the former with it. Thus a top-performing procurement organization would carry out all of the procurement roles, deftly applying them and increasing the functions value accordingly.

It is true to say that there are many procurement organizations that operate in the lower box in Figure 2.2. They carry out the very basic roles of procurement: to obtain the right things, at the right time and right place for the right price and right quantities and quality. To many people in business this is the accepted view of procurement; nothing more and nothing less.

Procurement value proposition has come about as procurement and its role in businesses has evolved. Its value is defined in terms of generating more value for monies spent on suppliers. This is typically achieved by either less expenditure or deriving greater impact from the monies spent. Doing so requires that procurement offers a set of services that are valued by stakeholders. To define levels of value, we have a scalar of five principle value propositions:

• supply assurance;

• cost reduction, which covers two aspects:

– purchased costs;

– total costs;

• demand management;

• value management – where procurement teams are tapping supply market innovation to support the strategic objectives of the business.

What is apparent is that the best procurement organizations focus on generating value instead of generating transactions. It is often said that the largest cost in procurement is the opportunity cost of not freeing up staff to perform higher-value activities. The question then becomes: how do procurement organizations move away from the transactional activities to spend more time on higher-value activities? This question brings into play one of the fundamental questions in procurement: the make versus buy decision. It raises too questions around how procurement is actually measured. Is procurement measured on its diverse value contributions or simply on reducing spend magnitude?

Procurement’s aspiration to move up the ladder has to be deliberate and it must be sustained. As the business begins to expect more from procurement it has to continue to deliver. At the same time, chief experience officers (CXOs) are likely to give the CPO and the procurement organization increasingly more latitude in the transformation. However, it is not just about giving and getting more of the same thing. As procurement’s services evolve, so will its role and its brand.

While brand management might seem a little far-fetched, procurement is a professional services organization and needs deliberately to create and execute against the promise of its brand. Otherwise, the brand will be created on prejudice, perception will become reality, and procurement may well find itself doomed and lapsing back to its historic role.

The differences in the brand ‘promise’, or role, of a new procurement organization makes it difficult to compare an internal satisfaction score across businesses, simply because the services offered are highly likely to be different. A business where people are saying that procurement is excellent because it scrambles well or places purchase orders (POs) well is far worse than a business where the prevailing view is that procurement is doing a good job on its broad array of strategic supply services. In other words, internal satisfaction is an effectiveness performance measure focused on quality set against a service level – not the quality of the procurement service portfolio itself. So, in a very real sense, it is limited.

This evolution is not an easy process, especially when procurement’s desire to perform higher-value activities will undoubtedly conflict with peoples’ perceptions of what it should or can do. Many businesses do not want procurement to move beyond its ‘accepted’ role – the ‘table-banging’ negotiator or buying stationery. They don’t want procurement to play a role in demand management, specification management or continuous improvement activities.

Some obvious examples of strategic projects for which procurement support should constantly be called upon to add its arsenal of capabilities include:

• pre-merger planning;

• post-merger integration;

• asset rationalization;

• product/ service design rationalization, and so on.

This expansion of procurement’s circle of influence should occur across the whole business, including operating units, regional groups, functional partners, senior management, regulators, suppliers, and for the benefit of procurement staff too. After all, stakeholders are not just budget holders.

To reiterate: this process has be a continuous evolution and there are many barriers to push through. The biggest of these issues tends to be procurement’s ability to create an operating model that allows it to evolve its value proposition and create substantive change in its own organization. Turf wars are another major barrier. Immediately you cross the line into processes that other functions within the organization are performing – the in-fighting begins. In fact, this issue gets more complicated with the emergence of global business services organizations that are continuously pulling more processes inside them. Examples include procure-to-pay (P2P) transaction processes, analytics, continuous improvement – and even procurement is occasionally being turned over to them.

How should we measure procurement’s performance?

One single and rather compelling metric of procurement performance is procurement return on investment (ROI). This can be expressed as the ratio of traditional expenditure cost savings as a percentage of spend with suppliers divided by the annual investment in procurement processes.

Another way of measuring procurement’s performance might be to look at the impact of maverick spending, which can be described as a ‘yield’ loss on the business’s negotiated savings figures in any year. In doing this we must of course assume that the procurement organization is not overstating its savings. This could be a possibility if procurement is unable to track savings to the bottom line; but a good procurement organization should be equipped to do this. Doubtless people will squabble over this issue, claiming that it simply isn’t worth the effort when considered against attracting new deals. However, to improve procurement’s credibility with budget holders an increase in terms of the validity of procurement’s claimed savings would not go amiss.

Finally, in terms of quantitative measures, which these measures invariably are, measuring spend influence is perhaps the favourite. Another very important issue relating to the quality of procurement’s spend influence will clearly be dependent on when they become engaged in the spend cycle; a loss of leverage, and thus business impact, because of ‘late-stage’ procurement involvement is fairly common in most businesses.

However, times are changing and procurement is increasingly influencing new spending areas. In fact, the economic downturn that began in October 2008 and the cash-strapped years that followed gave procurement an opportunity to bring greater influence in new spending areas and perhaps, too, to develop new policies that were not possible before.

Looking forward

Whether in one’s personal or professional life, we all need a vision of where we will be or where we want to be in five or ten years’ time; and the same holds true with procurement as a function. Procurement in the future will likely be substantially different to what it is today. To ensure this, one’s vision for procurement must be clear and achievable. Moreover, procurement’s visibility, credibility and resilience within business are critical, if it is not to be subsumed into or by another strategic business unit (SBU).

Increasingly the work of the procurement professional is knowledge-based, virtualized and globalized. The idea of ‘everything as a service’ will make its way into these internal end-to-end processes via a clear trend towards global business services (GBS) organizations – to which procurement may have to some day report or, as is more likely, complement. The deliberate design of these value chains requires a vision, a service delivery strategy and a supporting service delivery model. It will be incumbent on procurement professionals to demonstrate that they have the associated capabilities not only to ensure that the vision can be implemented but also to signal to the rest of the business that they are the natural owners of this aspect of the value chain.

As procurement broadens its vision, rethinks its strategies, tunes its service delivery models and shores up its capabilities, it needs to do so while continuing to execute and also to perform this transformation as efficiently and effectively as it can.

In the case study that follows, we identify the trajectory taken by one organization, Biogen Idec, as they sought to improve value and transformed themselves into a new procurement capability.

Case study: motivation for change – Biogen Idec’s transformation to world-class supply management

Many organizations have begun to create centralized supply management organizations to improve leveraging of spend and improve alignment with executive stakeholder objectives. Targeted first in the automotive sector in the 1980s, sourcing has spread rapidly through a number of industries including electronics, pharmaceuticals, oil and gas, financial services, insurance, but still has a few remaining holdouts in the biopharma sector. Not only are these organizations younger in maturity than their ‘big-pharma’ counterparts, but they also face imposing challenges in the form of good manufacturing practice (GMP), a complex clinical trials process that is global in scope, temperature-controlled environments, and complicated manufacturing processes.

The first wave of strategies typically identified by these organizations embarking on strategic sourcing is often targeted at cost reduction through volume consolidation and leveraging of an organization’s total spend, followed by supply-base reduction and longer-term contracting. Yet as organizations mature, executives recognize that supply management must adopt a more strategic set of value propositions beyond leveraging spend for cost savings. Moreover, supply management is now being asked to build rapid insight into customer requirements, and translate this rapidly into product offerings with increased reliance on outsourced capabilities in the supply chain.

In 2009, Biogen Idec (BIIB) underwent a major shift in the way it operates its supply chain. What began as a ‘grass-roots’ transformation effort produced strong early results in the form of cost savings (an initiative that was deemed important by its executive management team). As the effort grew, however, it produced exemplary results beyond simple cost savings, sustaining the momentum and moving the organization to higher levels of process performance. This was accomplished with comparatively little automation of the process, but focused instead as stakeholder engagement as a critical enabler of improved supply chain performance.

In June of the same year, an assessment of supply chain maturity was performed across the Production, Operations and Technology (PO&T) group at Biogen, and significant opportunities for improvement identified. Supply chain processes were deemed to be at an ad hoc level, with resulting inefficiencies and uncontrolled spending prevalent in many parts of the organization. A summary of the current state was reviewed by leadership team who agreed that there was no way to go but up. Specifically, the following observations were made in six critical process maturity components:

Governance: at the time of the gap analysis, there was a lack of formal executive oversight of major sourcing and supply chain initiatives. Sourcing was largely disengaged from stakeholders, and were brought in at the last minute to ‘paper deals’ manually. Suppliers typically worked closely with stakeholders to drive specifications and pricing, with little engaging of supply chain teams in market analysis or cost management.

Procure to pay: less than 40 per cent of spend was actively managed and properly contracted, there were some very basic metrics to track spending or savings, which had the potential to overlook significant leakage and maverick spending. Approvals typically took in excess of 45 days, due to lack of due diligence around documentation and manual systems, contract compliance and an ongoing issue at board meetings.

Category management: a small number of category strategies was under way, but formal category management (CM) processes had not been rolled out. Senior category managers (SCM) had little opportunity to demonstrate the value of market insights and rationale for supply base optimization, as there were few resources available to draw on. Finally, while supply chain risk was informally recognized, few metrics or contingency planning were in place to drive risk management activity, and planning meetings were rife with firefighting activity.

Supplier relationship management: with little governance and no formal governance mechanisms, it was not surprising that supplier selection and evaluation occurred on an ad hoc basis by stakeholders. Inconsistencies in selection criteria, relationship owners, lack of market price benchmarking, and informal performance measures led to poor business decisions and exposure to contracting risks. A large supplier base had developed, causing an explosion in the workload for managing the suppliers.

Performance measurement: no formal key performance indicators (KPIs) were employed to track supply chain performance around critical processes such as spend under management, supplier performance, contracting status, cost savings, visibility of service level metrics, or multiple sourcing agreements with suppliers across sites.

Talent management: because of their high workload, SCM associates were often stuck on transactional activities. Not only was the function under-resourced, but despite their hard work associates received derisive reviews from their business partners due to disruptions and late deliverables. In addition, new people entering the team were in some cases cast-offs from other business partners, and there were no formal career path development activities occurring.

When it came to execution, several steps were taken to add structure and discipline, with the underlying theme that sourcing, in a decentralized form and in concert with good business processes, could yield a lot of value and transform the supply chain. These actions are documented below.

Governance and stakeholder engagement

A PO&T leadership meeting in July 2009 established a road map for delivery of results aligned around core deliverables. A sourcing council was formed within the operations group that focused on all direct materials and services – direct here being defined as any material or service being utilized within the process and production. Three working groups (raw materials, change management officers (CMOs), and distribution/ logistics) were established to drive category strategies. The decision was made to establish a decentralized but dedicated direct (GMP) focused sourcing organization, with team members placed in proximity to stakeholders for maximum interaction and dialogue. A consistent sourcing approach was developed to ensure that strategies were data-driven and aligned with stakeholder expectations.

Recognizing the need to drive stakeholder engagement, a supply chain mission statement was established and communicated through ‘road shows’ with stakeholders. The message was that supply chain’s objective was to work more closely with functional groups to reduce costs, reduce risk and maintain compliance. A two-tiered structure was established, with one group focused on strategic sourcing, and another on procurement transactions and analytics. The biggest change, however, was the active application of sourcing council involvement on supply chain policies and processes. Major supply chain projects were reviewed quarterly by the sourcing council to ensure that projects were sanctioned and resourced appropriately.

A major change in the way that the supply chain engaged with stakeholders involved a culture of data-driven business case development. Stakeholders were engaged in major sourcing decisions, and supply chain associates adopted a culture of bringing relevant data to the table to establish sourcing and planning decisions. In every sourcing decision, market intelligence, spend forecasts, contract data and technical requirements were systematically applied to build a convincing rationale in support of decisions. Although there was some resistance to the structure imposed by a sourcing governance framework, it quickly became clear that early supplier engagement was beneficial to the business teams. Today, technology development and other units voluntarily bring category managers ‘into the loop’ early in the project initiation stage, as they see the benefits of this approach. One of the important change management principles that supported this was that all benefits (cost, etc) achieved by the team were directly attributed to the business unit, not the sourcing team, and savings were validated by finance for presentation to senior leadership. Finally, suppliers are now much more willing to work with BIIB sourcing teams, and have gone so far as to recognize that ‘BIIB’s request for quotations (RFQs) are the clearest and easiest to work from in the industry!’

Procure to pay systems

One of the most important changes that occurred to drive improvement was the use of a PO recommendation memo, which is a standard template that captures the essential justification, fair value and rationale for the purchase. All purchase orders and requisitions that do not require vice president (VP) signature authority are routed to a single individual tasked with recording and tracking the amount. This has led to significant reductions in approval lead times, as approval levels have been raised given the increased confidence in the approval process and documentation. Physical copies of contracts are now sent to an individual who sorts them through an intelligence nomenclature that allows quick retrieval. As a result, mid-year reviews and reports for business managers who wish to track spend against contract are now easily produced and are accurate. In addition, 100 per cent of spend managed and under contract. PO memos capture rationale and due diligence, and approvals are routed quickly in less than 15 days. Contracts are reviewed, catalogued and tracked against actual spending, and reports generated for business directors on a timely basis.

Category management

Coming out of a 3Q 2009 short course, a handbook was used as a guide for teams to begin the category management development process. Category teams were formed in GMP, Technology Development, and Distribution/ Logistics. The handbook provided guidelines to assist the team in the core steps of business requirements development; technical requirements; supplier evaluation; and supplier selection and sourcing strategy. A standard set of strategy templates was developed presenting the current situation, analysis and business case. As the number of sourcing projects increased, stakeholders were asked to engage and participate in strategy development. With supply chain bringing believable and accurate spend data and technical requirements to the table, stakeholders’ confidence in their ability grew, to the point where they now actively seek out PO&T for all major sourcing initiatives. All sourcing projects are supported by a strong business case, and major strategies are reviewed by the sourcing council. The business case is comprised of spend analytics, vendor risk analytics, additional market intelligence, ‘should-cost’ models and vendor continuity reports. One of the two biggest additions during this process was the development of market intelligence resources, including outsourcing partner Beroe and access to six new market databases. Whereas in the past supply assurances were based on the relationship, selection (a function of the supplier’s marketing strength) and tribal knowledge, and price was proposed by the supplier, the teams became much more proactive in building strong negotiating positions and buy-in based on solid data and analytics. Once selected, new suppliers are vetted in partnership with a rigorous qualification process. For suppliers with an above-average risk profile, contingency plans are integrated into contractual terms and conditions, or alternative redundancies identified.

Supplier relationship management

Supplier selection is developed by category teams led by sourcing specialists, based on business requirements and fair value, not on relationships. Supply chain is actively engaged in the early stages of project identification and specification, with market-based price and cost date employed to ensure fair value. Should-cost models and supplier scorecards are used to govern the supplier relationships after contract sign-off.

Performance measurement

Client-focused metrics are established and tracked for all sourcing engagements. Spend against contract budget is regularly communicated to business partners. Metrics include rolling spend, cumulative savings, per cent on preferred suppliers, number of projects, business impact, fair value assessed, and supply risk. P2P metrics around PO compliance and supplier performance is also tracked. This visibility and transparency has created significant benefits, most importantly that senior leadership feel that supply chain is in a managed, controlled state and that discipline has been used in the way that teams make decisions.

Talent management

PO&T associates have been augmented significantly with highly qualified technically proficient people, and former associates have expressed a renewed esprit de corps. Associates are less focused on transactional activities and instead are engaged on strategic management of critical outsource relationships, cost management, and risk monitoring and control. Several individuals have been recognized as high potentials across the organization, and senior leadership has formally acknowledged the contributions of the team to BIIB’s competitive future.

Summing Up

Supply chain at BIIB underwent a significant transformation in its critical processes. Current validated savings (effective September 2010) exceed US $9 million and current avoidances exceed $4 million, amounting to almost $15 million of savings on managed spending of $150 million.[!case study ends!]

Some conclusions

Procurement’s value proposition to the business is inextricably linked to performance and capability. Capability enables better performance, as well as adding value. The impact of value and performance on the business requires procurement to maintain a high profile and the appetite to deliver ever-broader services.

It is also critical that procurement treads carefully. Misalignment or the possibility of disintermediation will create very real issues across the organization. Procurement’s vision of its high-value proposition without the requisite level of performance and the right relationships is nothing more than an empty promise. Well-developed procurement capability without the requisite performance levels is an opportunity missed and money down the drain.

For procurement, to exist in a space where a low level of value to the business is all that is expected of them might be appear safe or even comfortable today. However, there is a real possibility that if this situation were to remain the same then, before very long, procurement will tomorrow become a commodity – and possibly redundant the day after that.

If we contemplate a scenario of performance without capability then the usual outcome is characterized by unsustainable heroics, which are neither scalable nor repeatable. The best procurement organizations of the future will have the greatest relative strength in core process capabilities – supported by high-impact technology to support high-impact processes.

Both the business, and procurement, want activity shifted to higher-value propositions, but current measurement systems and metrics do not encourage this. Many procurement organizations execute well to the traditional metrics, such as purchased cost savings and supply assurance goals, but are still considered decidedly mediocre when it comes to higher-value services. The greatest capability gaps are in working capital management, involvement in the business ‘process sourcing’ decision, and in tapping supply markets for innovation.

Finally, there is a clear need for procurement’s operating model to catch up with the times. Frankly, the typical procurement model has become stale. With no historic permission, no mandate or accountability, and weak IT support, there is a clear need to push beyond basic supply-centric, ‘n’-step procurement methodology. Customer and demand management adoption is critical to procurement realizing its potential and delivering value, as is earlier and deeper involvement in stakeholder processes, including involvement with external suppliers. It is fair to say that spend analysis, cost modelling and strong procurement ‘execution’ capabilities are the prerequisites of a value-adding procurement organization.

In this chapter we explored the concept of value, and identified how procurement can move up the ladder to go beyond cost savings, and drive towards true value improvement. In the following chapters we go on to depict how global trends are leading to profound changes in the thinking behind corporate strategies. We then discuss the drivers of the shifts in global business, which we call the ‘game changers’. These are essentially creating an entirely new set of rules for playing the business game. We also introduce a practical approach to change, using the ACE model, because in this game, doing nothing is a decision that some may choose to take – and that is a decision that will ultimately cause you to lose the game.

Click here to read a Q&A with the authors.

Excerpted from The Procurement Value Proposition: The Rise of Supply Management by Gerard Chick and Robert Handfield 2014. Reprinted with permission of Kogan Page. All rights reserved.

About the authors: Gerard Chick is Chief Knowledge Officer at Optimum Procurement Group, a procurement outsourcing and consulting company. He is a speaker and writer on business and procurement issues and has written for journals such as CPO Agenda, Supply Management and Procurement Professional. Chick is also a visiting Senior Research Fellow at Curtin University in Perth, Australia, a visiting Fellow at Cranfield School of Management and a member of the Logistics and Operations Management Board of Cardiff Business School. He can be reached at [email protected].

Robert Handfield is the Bank of America University Distinguished Professor of Supply Chain Management at the North Carolina State University Poole College of Management, and director of the Supply Chain Resource Cooperative. He has consulted with Fortune 500 companies, including Caterpillar, GlaxoSmithKline and FedEx, and he has published more than 100 articles in top management journals, including MIT Sloan Management Review, the Journal of Product Innovation Management, and the Journal of Operations Management. He can be reached at [email protected].

SC

MR

Latest Supply Chain News

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Humanoid robots’ place in an intralogistics smart robot strategy

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- More News

Latest Podcast

Explore

Explore

Latest Supply Chain News

- How CPG brands can deliver on supplier diversity promises

- How S&OP provides the answer to in-demand products

- AI, virtual reality is bringing experiential learning into the modern age

- Humanoid robots’ place in an intralogistics smart robot strategy

- Tips for CIOs to overcome technology talent acquisition troubles

- There is still work to do to achieve supply chain stability

- More latest news

Latest Resources

Subscribe

Supply Chain Management Review delivers the best industry content.

Editors’ Picks